- Home

- Q. Patrick

Cottage Sinister Page 6

Cottage Sinister Read online

Page 6

“Mother, this is the Inspector. Inspector—?”

“Inge,” said the Archdeacon.

“Inspector Inge. He’s come to help us. But first, of course, he’ll want to ask us a few questions.”

“Help us?” quavered Mrs. Lubbock. “Help us?” and she fixed incredulous eyes on the Archdeacon. Then she collected herself and made him welcome, while he murmured a few words of sympathy and condolence.

“Here,” said Lucy, “take a chair. I’ll clear up tea later.” She drew two chairs away from the table to the window, and placed the Archdeacon between herself and her mother, facing the room, while Buss sat down by the door and mopped his face with a handkerchief that had seen better days. The Archdeacon drew out his note book and settled into his seat, for all the world like a cleric about to do masterful things to a skein of wool.

“It gives me great pain to distress you, Madam,” he said to Mrs. Lubbock in his most soothing voice, “but of course you, above all others, must be anxious to get to the bottom of these—er—curious and tragic occurrences.”

“That I do, sir,” said Mrs. Lubbock, leaning forward with an unexpected vehemence. “And if ever you find who did it, sir—”

“All in good time,” said the Archdeacon, and referred for a second to his notes.

Mrs. Lubbock shivered. “Not too much time, sir. I’ve a fear in my bones.”

“H’m,” said the Archdeacon. “Yes. The doctor who’s in charge. Could you tell me his name?”

“Dr. Hoskins,” said Mrs. Lubbock. “It used to be Dr. Crampton, sir, but since he left we’ve had Dr. Hoskins.” The Archdeacon turned to Lucy with a quick glance. Involuntarily her lips moved in answer to his question.

“Isn’t that so, Miss Lubbock? Or did you mention a different name?”

“No, Inspector. My mother is quite right. Dr. Hoskins is the doctor in charge.” Her voice was steady, but the faint flush in her cheeks did not escape the Archdeacon.

“We’d better have Dr. Hoskins here if it’s possible,” he said. “Buss, would you be good enough to see if you can find the doctor, and bring him along if he’s free to come?”

Buss rose and expanded. “Yes, sir. I shall expedate at once. God bless you, ma’am. I’m truly sorry.”

Mrs. Lubbock bowed her head in a simple acknowledgment, while Lucy’s unseeing eyes followed the Constable’s broad back as he strode down the path and out at the garden gate. Then the Archdeacon asked the two women a few questions establishing the hours of the deaths (approximately in Amy’s case, exactly in Isabel’s), and, in some detail, their manner. Lucy answered him promptly and firmly, mentioned the Dormital tablets, and occasionally lowered her voice to spare her mother some painful incident. But Mrs. Lubbock showed an extraordinary fortitude, surprising even Lucy by her eagerness to enlist the detective’s every power. It seemed as if her whole nature, overwhelmed at first by grief, had responded now to an impulse of indignation the more vehement because it was so entirely alien to the usual tenor of her ways.

“You must find out,” she pleaded. “There may be more to come. And it seems like my Amy had a presentiment, too, leastaway, she told me on Sunday evening that Isabel had been seeming strange and distant like. And then there was the candle grease like a shroud! It doesn’t matter for me. I’m old. But here’s my Lucy, with all her life ahead of her. I’m afraid to have her staying here. Terribly afraid, sir.”

“And I for you, Mother,” said Lucy in a half whisper.

There was a pause, in which the Archdeacon’s eyes traveled about the room, taking in all its details and resting finally on the table where lay the remains of a frugal tea. He had ascertained by his questions that in each case tea was the last meal eaten by the victim, and he looked with interest at the scattered tea things. Then he got up and went over to the table to examine them more closely, but Lucy, reading his thought, explained that the usual tea things had been locked away unwashed in a cupboard after Isabel’s death.

“Ah,” said the Archdeacon quickly. “And who has the key?”

“Dr. Hoskins, I believe. I wasn’t here at the time. I think I had fainted.” She gave him an apologetic glance. “It was late last night. Dr. Hoskins and Dr. Crosby had come back from taking—from taking my sister Amy to Taunton for the autopsy—where they took Isabel this morning. But this morning I was too busy attending to my mother to hear much about last night. I believe there was something that puzzled them. Will Cockett would know, too.” She passed her hand across her forehead as if she were searching for something that hovered just beyond conscious memory.

“Then we must wait for the doctor,” said the Archdeacon, resuming his chair. “But, Miss Lubbock, you mentioned two names that were new to me. Supposing we fill in the time till the doctor comes by running through a list of the people who have come into the cottage in the last two days, and might have been in a position to—er—to tamper with anything.” The Archdeacon avoided the word “poison”. (“Don’t frighten people” was one of his fundamental maxims.)

Lucy turned to her mother. “I was out most of Sunday,” she said. “Can you remember?”

“Let me see,” Mrs. Lubbock muttered. It was evidently an effort for her to push her thoughts back to anything that had occurred before the tragedies.

“I was at the hospital,” Lucy explained. “There was an urgent case—we were fighting to save a poor old man’s life—and 1 was gone from breakfast till tea time. When I came in my sisters had arrived from town and were having tea with Mother.”

“Yes,” said the old lady. “That’s so. They’d arrived just a little while before tea, and the only other people earlier in the day were Sir Howard and Miss Darcy who dropped in after church in the morning. Very affable they were, too, sir.”

“Sir Howard, yes,” said the Archdeacon, visibly impressed by this act of condescension. “But who is Miss Darcy?”

“Miss Vivien Darcy, sir. They do say she rides a trifle hard to hounds, and is very new-fangled in her notions. But she’s kind, sir, and always has a word for an old woman like me. And they do say, too, that she’s sweet on the young squire, though I daresay it’s nobbut because the two of them were children together.”

“Yes,” said the Archdeacon, scribbling in his book. “And then?”

“There were others after tea,” said Lucy. “But I went back to the hospital before they came. Who was here, Mother?”

“Before you went, dearie, of course there was Mr. Christopher.”

“Yes,” said Lucy. “He did take tea. I’d forgotten. My mother means Dr. Crosby,” she explained to the Archdeacon. “He called for me on the way to the hospital.”

“Dr. Crosby? Any connection with the family at Crosby Hall?”

“Yes, sir,” said Mrs. Lubbock. “He’s the young squire I was speaking of. But he’s new-fangled, too, and must needs be off doctoring, so we have to call him Dr. Crosby, though dear knows he’s always Mr. Christopher to me, and Sir Christopher as is to come.”

“I see,” said the Archdeacon, further reconstructing his picture of the aristocracy, a picture which had already been sadly altered by Lady Crosby. “And he and Dr. Hoskins work together in the village.”

“Oh, no,” said Lucy quickly. “Dr. Crosby is simply here on a holiday, and happens to have been assisting Dr. Hoskins because he takes a friendly interest in what goes.on in Cros-by-Stourton. He has no responsibility in connection with these—er—deaths.”

“Quite,” said the Archdeacon. “Most natural. And I suppose you didn’t notice anyone hanging about the house on Sunday afternoon? Any stranger?”

“I did notice a man standing in the road looking at Lady’s Bower. It must have been at about six o’clock, I think. I remember wondering he didn’t move on. But he soon did. I’m quite sure I’d never seen him before. But many pause to look at Lady’s Bower, you know.”

“I don’t wonder,” said the Archdeacon with an appreciative glance about the room. “And your mother didn’t see him?”

&

nbsp; “No, sir,” said Mrs. Lubbock. “I never heard tell of him till this minute. And poor Isabel and Amy never mentioned having seen anyone.”

“I see,” said the Archdeacon thoughtfully. “And now I wonder if you could tell me of anyone else dropping in after your daughter and Dr. Crosby left?”

“Well, sir, we don’t get many visitors as a rule, leading a quiet life as we do, and I was quite surprised to see the neighbors coming in so friendly like. There was Mrs. Greene from the post office, and Miss Sophy Coke, and poor Will Cockett, who was always sweet on Amy, sir, since they was just a boy and girl. He’s the village carpenter, sir, and a very nice fellow indeed. I’ve often wished she’d have him, though perhaps he’s a little solemn. But our Amy had good spirits enough for two, and was such a good girl, sir, they all said so.”

Mrs. Lubbock, giving way again to grief, leaned back in her chair and began to cry softly, and Lucy took up the story:

“That was all that happened—on Sunday. They went to bed early, and there wasn’t a sound when I came back from the hospital, except that little cough of Amy’s. The next day, yesterday, there were only the two doctors in the morning. And after lunch Sir Howard and Miss Darcy looked in again for a moment. Then later some friends came in—there must have been about half a dozen altogether—Mrs. Greene and Miss Coke and Will Cockett and Dr. Crosby and one or two others—but they stayed only a few moments and didn’t take tea, except Will Cockett later. But first Dr. Hoskins came with the ambulance from Taunton, and he and Dr. Crosby went away with Amy.”

She gave the names of the other visitors, and then paused for a minute while the Archdeacon considered and made notes.

“I see,” he said finally. “That left only you two and this Mr. Cockett?”

“And Isabel,” said Lucy quietly.

“Of course.” said the Archdeacon.

“Well, we had tea,” the girl went on. “And then after a while I got up to light the lamps, and—and—oh, I’ve told you the rest.”

“Hm,” said the Archdeacon. “I’d like to see Cockett if he’s available.”

“Shall I go and fetch him?” asked Lucy, moving towards the door.

“No,” said the Archdeacon with a benign gesture. “It’d be more help if you’d stay here and—er—corroborate the doctor, you know.”

He then asked to see the rest of the cottage, and Lucy led him upstairs to show him the bedrooms, two of them the more glaringly untenanted by reason of the clothes and toilet articles that were casually lying about as if their owners had just stepped out. Isabel’s garish kimono lay untidily across-the foot of her bed, and one or two bright colored dresses of expensive looking material were flung over the back of a nearby chair.

“Nothing has been changed?” asked the Archdeacon, noting a half-unpacked suitcase in Amy’s room.

“No, Dr. Hoskins suggested that we leave things as they were.”

“Good.”

He made a rapid survey, and they both descended the stairs again just as a knock at the front door announced the doctor. Lucy greeted him and introduced him to the Archdeacon, who then sent Buss in search of Will Cockett.

Dr. Hoskins, looking worn and upset, shook the Archdeacon’s hand with an expression of relief.

“I’m no end glad to see you, Inspector. Good evening, Mrs. Lubbock.”

The Archdeacon took in at a glance the doctor’s shabby clothes, his keen, earnest eyes behind a huge pair of hornrimmed spectacles, and his hurried, nervous movements.

“I’m glad to see you, too,” he said heartily. “We’ve been waiting for your help in several matters.”

“The autopsy reports, I suppose? And the report on the Dormital tablets? We’re checking up on their formula, you know.”

“Yes,” said the Archdeacon. “Miss Lubbock mentioned that you were.”

“Well, I’m afraid that we’ll have to wait until tomorrow morning for all that. Both reports are promised by ten o’clock. I tried to hurry them up, but that’s the best they could do.”

The Archdeacon was disappointed, but not unduly. A large patience was one of his major assets. “If you wait long enough,” he used to say, “almost any criminal will give himself away.” And the Archdeacon had often waited long after others would have thrown up the case—and waited to very good effect.

He asked for the doctor’s corroboration on the times of the two deaths, and then suggested a rendezvous for the next day.

“Supposing I see you at ten o’clock in the morning, then. Shall I call at your office?”

“Excellent.”

“And now I believe there’s another little matter where you can help us. About yesterday’s tea things….”

“There is indeed,” said Dr. Hoskins with a grim inflection which Lucy and the Archdeacon were quick to catch.

The doctor drew a small key out of his pocket and handed it to the Archdeacon.

“I apologize, ma’am,” he said to Mrs. Lubbock, “for running away with your key. But I thought it for the best, under the circumstances.”

“Oh, yes, sir,” said Mrs. Lubbock vaguely.

The doctor led the way to the kitchen, followed by the Archdeacon, while Lucy remained with her mother. As soon as the two men found themselves out of hearing Hoskins turned to his companion and laid a hand on his arm.

“I’m thankful you’ve come. There’s something all wrong about this. God alone knows what it means.”

With a nervous jerk he indicated a cupboard in the corner. The Archdeacon opened it slowly and drew out a tray with a jumble of tea things. For a moment he looked at the tray intently without seeing anything worthy of comment; a teapot and kettle, a tea caddy, a milk jug half full of curdled milk (the night had been hot), a sugar bowl nearly empty, an almost untouched plate of bread and butter, four spoons, four saucers, and four empty cups. Then suddenly his quick eye caught the salient fact, and he turned on the doctor with an unwonted vehemence.

“Whose cup was that?” he demanded, pointing to the one which showed no vestige of any dregs of tea. The doctor met his eye with a dogged stare.

“That was Isabel Lubbock’s cup,” he said.

The Archdeacon whistled softly.

“Who was with you when you made this discovery?”

“Dr. Crosby and Will Cockett. Crosby had just driven me back from Taunton in his two-seater, and it must have been nearly midnight. Cockett was waiting for us at my house, and asked us to come at once to Lady’s Bower, which we did. You know what we found—Isabel Lubbock dead, and the other two as good as—for the moment. After we’d got them upstairs, Crosby and Cockett and I had a look at the tea things, still on the table of course, and we asked Cockett who’d used which cup….”

“H’m,” said the Archdeacon. “Rinsed out, perhaps. And could Cockett throw no light on the rinsing of this cup, if rinsing it was?”

“Rinsing it was, all right. I asked him, just as we were leaving, whether he remembered if Isabel Lubbock had drunk tea at all. Thought it just possible she’d not taken any, you know. Cockett said he remembered noticing just that afternoon how strong she took it….”

“And Miss Lubbock? Have you questioned her?”

“No, I haven’t. I started to this morning, when I was here with Crosby. But Crosby stopped me. Said something like this: ‘Can’t you see, man, she’s absolutely done up?’ And I daresay he was right. She hardly understood when you spoke to her.”

“And Cockett? He hasn’t asked her?”

“I doubt if he’s been in today. His work keeps him till tea time.”

“H’m.” A tiny frown puckered the Archdeacon’s forehead as he carried the tray back into the front room. Lucy looked up as he came in, and glanced unconcernedly at the tea things. He set them down on a table in a far corner of the room before he crossed to her chair with a confidential expression.

“Everything seems quite all right in that quarter,” he said. “The only thing I want to ask you about is whether any of you four who were here yesterday

went without your tea. One of these cups appears not to have been used.

Lucy considered for a moment.

“I really couldn’t say. I know I drank tea. And I know Mother always does. And I think Will does, too. But sometimes Isabel doesn’t take anything. Perhaps she didn’t yesterday. I don’t remember. Do you, Mother?”

“What? What’s this?”

“Do you remember, Mother, if Isabel drank tea yesterday afternoon?”

“I daresay she did. I think I should have remembered if she hadn’t. But sometimes she doesn’t. And sometimes she drinks just hot water. Her digestion, you know, sir. It was never very strong, poor girl. She was always taking things for it. Dear me, I couldn’t say.”

The Archdeacon drummed with his fingers on the back of a chair. “Very trying, Madam, a bad digestion,” he said absently. Then he turned to the doctor, who had been standing in the doorway that led to the kitchen.

“I don’t think there’s anything further to be done tonight, Dr. Hoskins, except for a word with Buss and Cockett. I’ll see that these things are sent Op to the Yard for analysis. So if you’re busy I won’t keep you—”

“Thank you,” said the doctor. “I think I’ll be off, then. I have some patients waiting in the surgery. I’ll expect you at ten in the morning, and then when we’ve some definite ideas of what drug was used I daresay you’ll want to comb the village to find out if it’s available. Good-night, Mrs. Lubbock. Good-night, Inspector.”

He stepped out into the gathering June dusk, and nearly collided with Buss and Cockett on the threshold.

“I’m so sorry. I didn’t see you. Good night,” and he hurried off.

Cockett faced the Archdeacon’s look with a stolid stare, while Lucy rose to say good-evening and to light the lamps. Cockett went to help her, and as he did so the Archdeacon drew Buss aside to ask if there was a train up to London that night. Finding that there was, he explained that he wanted the tea things sent up at once to the Scotland Yard Pathologist. Buss scratched his head and departed in search of a ‘rapacious basket’ and some ‘emetic containers,’ leaving the Archdeacon to resume his scrutiny of Cockett. The village carpenter was a man of heavy build, slow of motion and slow of speech. This much the Archdeacon saw at once. Then, when the lamps were lighted, and Lucy was again sitting beside her mother, he walked across the room to the corner where Cockett was standing motionless, staring at the disordered tea things of the day before. The Archdeacon laid a hand on his shoulder and spoke softly:

Death Goes to School

Death Goes to School Hunt in the Dark

Hunt in the Dark The Cases of Lieutenant Timothy Trant (Lost Classics)

The Cases of Lieutenant Timothy Trant (Lost Classics) Death for Dear Clara

Death for Dear Clara S.S. Murder

S.S. Murder Death and the Maiden

Death and the Maiden The Grindle Nightmare

The Grindle Nightmare Cottage Sinister

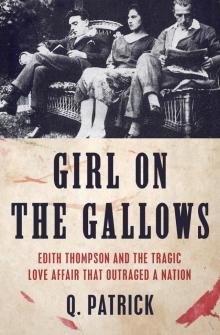

Cottage Sinister The Girl on the Gallows

The Girl on the Gallows