- Home

- Q. Patrick

The Grindle Nightmare

The Grindle Nightmare Read online

The Grindle Nightmare

Q. Patrick

Chapter I

As far as I was concerned it all started on a certain Saturday evening in late November or early December. I am sure it was a Saturday because Toni and I had come home from the hospital earlier than usual. I am also certain that the fall was well advanced, for I remember that it was almost dark when we passed the forbidding grey walls of the Alstones’ house. Unfortunately, however, I have no record of the exact dates. Later on, when things began to assume such uncanny proportions, I had reason to wish that I had been more observant of the details of those first strange occurrences in Grindle Valley. But, like most of my neighbors, I never suspected at the beginning that I could ever be more than an onlooker in the grim game whose opening play I ignored so completely on this particular Saturday evening.

As we drove homeward, it was obvious to both Toni and me that something was wrong. At first I thought it must be a hunt, but Grindle was a conservative spot and did its hunting at conservative times. Whatever the event, the whole neighborhood had turned out for it. There were little knots of villagers at every corner; in the woods we could hear the barking of dogs and there was an occasional gleam from a flashlight. Voices were audible even above the noise of the car, and everytime we caught a face in the headlights, it wore an unfamiliar, important expression. Of course, we should have stopped to inquire, but we were both tired and dirty. We had been working hard all day on a new group of experiments. Besides, it was the week-end and Valerie was coming in after dinner—Valerie and the Goschens.

“Didn’t know our rural areas were so densely populated,” grunted Toni, as he backed his car into our hideously inaccessible garage.

I thought no more about it at the time, but when I went upstairs to change for dinner, I could still hear shouts ringing across the valley. There was a restless, hopeless quality about them which gave me the impression that our neighbors had gone out to look for something which they knew they would never find—something of which they completely despaired. I remarked on this to Toni who had just emerged magnificent from the shower. But he only grunted again.

And what could one really expect but a grunt from Dr. Antonio Conti, one of the youngest and smartest professors of pathology in America? What was the excitement of a few villagers to a man who had been quite unmoved on the day when he first isolated Conti’s gram-positive organism from the blood stream of a patient with purulent endocarditis, and thus gave medicine one of its most valuable diagnostic aids?

But for all his grunts, Toni was no heartless scientist. I was sure of that when we had first struck up a friendship as research workers and instructors at Rhodes University Hospital. It was Toni’s influence that helped me to get in on all the most exciting laboratory experiments. It was he who had urged me to share with him the charming little farm house which he had rented from Seymour Astone in Grindle Valley some twenty miles out of town; and it was the handsome and aggressive Toni who borrowed from our richer neighbors guns for me to shoot with and horses for me to ride.

For some time now we had lived in style as only bachelors can. We were far more comfortable than Mr. Alstone with his lonely old grey house and fleet of servants; far more comfortable than the good-natured Goschens who were always overrun with wet-nosed children or noisy friends from town; far more comfortable than the emasculate Tailford-Jones whose wife was continually chasing after other men when she ought to have been making the best of a war-wrecked hero; and certainly far more comfortable than Valerie Middleton and her mother who lived on the penurious charity of Seymour Alstone. Our tidy house and well-ordered meals were the envy of the entire married community, and there was hardly a single one of our friends who had not at some time or other made passes at Lucinda—our efficient colored factotum.

She had just cleared away dinner and served coffee in the living-room when we learned the reason for the afternoon’s unrest.

“The Goschens are early,” remarked Toni, as a car drew up outside the door. I switched on the porch light, but it was not the Goschens nor Valerie who entered. Jo Baines, the Alstones’ gardener, stood at the door with a man whom I immediately recognized as the village constable.

Normally Baines wore the mournful expression of a man who has to provide for a large and growing family on the reputedly inadequate wages which Mr. Alstone paid his help. Tonight he looked even more tragic than usual—a circumstance which my medical mind immediately associated with the none-too-blessed event which I knew his wife to be expecting shortly.

“Excuse me, Dr. Swanson, but I thought I’d stop by and ask here.”

“Ask, Baines?”

The two men scanned our puzzled faces.

“Then you haven’t heard, Doctor?”

“Heard what?”

“About my Polly.” Baines’ voice was low. “She’s disappeared. Last night we think it was, though we can’t be absolutely sure. Anyhow, we’ve been hunting all day.”

“You mean to say that someone has kidnapped one of your children?” I could not make out whether the strained note in Toni’s voice came from polite indifference or incredulity.

“Hardly likely to be kidnapping, Dr. Conti,” interposed the constable. “Jo here isn’t exactly in a position to—well, they usually snatch for a ransom.”

“We don’t know much about it, Dr. Swanson.” Baines had turned his sad eyes on me once again. “When last seen, she was going out into the big meadow behind our cottage after her kitten which was always running away. She was afraid-like—well, you know how ’tis with animals round here.” He coughed apologetically. “Mark said he saw her calling to it about a hundred yards from the back door. That was about eight o’clock and what with Mrs. Baines not being like you might say quite up to looking after the children properly just now, no one thought any more about it till this morning when our Polly wasn’t there. You see, she’s old enough to put herself to bed now, but her bed hadn’t been slep’ in and neither she nor the kitten has come back home since.”

“So that’s what they were all out after this evening,” I exclaimed.

“Yes. Everyone has been lending a hand. Mr. Alstone let some of the colored help off from work this afternoon, and then his grandson was out too with young Mr. Foote from the medical school—they’ve all been searching, but we’ve not found hide nor hair of our Polly. Mrs. Baines is worrying herself sick and in her condition, as you know, Doctor …”

We made sympathetic noises and regretted that we had nothing tangible to suggest.

“I’m going to find her,” said Baines as he rose to leave, and there was a strange gleam in his usually mild eye. “I’m going to find her if I don’t eat a bite nor sleep until I’ve done it. There’s other things been going on around here lately, and I’m going to get to the bottom of it. I’m going to find my Polly.”

Throughout his speech I felt strangely moved. I say “strangely” because I am normally immune to any sort of psychic sensitivity and, at any rate, there is nothing particularly disturbing about a little girl failing to turn up at bedtime. But there was a certain quality about the man as he stood there, his shoulders bowed, his hands clenched at his sides, which made me feel that he knew, or suspected something of which we had no knowledge—something rather horrible.

“Funny!” remarked Toni after they had gone, “that when a poor family has seven children most of whom are congenital idiots, they should get all het up because one of them mercifully disappears. She was a nasty little girl anyway—one of the Baines’ less successful efforts.”

“Wait till you feel the touch of baby fingers about your collar, Dr. Antonio Conti,” I carolled.

“Baby fingers be!”

The intended obscenity was nipped in the bu

d by the arrival of Millie and Charlie Goschen, our nearest neighbors who own a fair-sized property adjoining the Alstone estate. They are decent people who ride hard, drink hard and are fundamentally incapable of shooting a brace of pheasant or pickling a batch of peaches without bringing in a share to us. Millie always reminds me of a maternal cherub, if such a thing is possible, while her large, burly husband is still as young and fundamentally as ingenuous as any of his own innumerable children. His passion for horses is rivalled only by his wife’s deep-rooted attraction for the candy which she is always swearing to cut out of her diet.

That night they were full of the Baines child—at least, Millie was. Although she succeeded in being flippant, I could tell she was taking it rather hard. She moved restlessly in her chair and completely ignored the peanut brittle which had been provided especially for her. I suppose that nowadays the specter of the kidnapper looms large in the mind of every well-to-do woman with children.

“I just don’t see what can have happened,” she was saying, throwing away her third cigarette, half-smoked. “I know the child was dumb, but surely there’s never been a child dumb enough to forget to come in for breakfast—if those poor devils have such a thing as breakfast.” Her plump face, usually so pink and shining, was slightly pale. “You don’t suppose someone’s run off with her, do you?”

I laughed reassuringly. “My dear Millie, people only steal for profit. By no stretch of imagination could you call Polly Baines profitable.”

Millie did not reply, and in the brief interval of silence that followed, I thought I heard a faint cry outside in the valley. I supposed it was my imagination, but as I strained my ears, it came again—long drawn and melancholy like some exotic night-bird. The others had heard it, too. Toni crossed to the window, pulling back the curtain.

“Mark Baines!” he said. “Mark shouting after his sister.”

It was rather eerie sitting there, listening.

Millie laughed nervously, and I guessed that her thoughts were still on her own flourishing family.

“Polly was always wandering about,” she began suddenly. “I think she must have been a fit fey. Time and time again, and quite often in the late evening, I’ve bumped into her creeping through our property. If anyone had been hanging around, waiting for a chance to grab one of our kids—they might quite easily have gotten Polly by mistake.” She lifted her hand from the table, and I noticed it had left a damp mark on the polished oak. “Something’s been wrong with this place lately. For two cents and a stick of chewing gum I’d pack up this minute and take the children into Rhodes before—before anything else happens. Of course, Charlie’s no millionaire, but …”

She broke off, laughing again. It was odd that a sane person like Millie with her healthy passions for riding, shooting and child-bearing should seem to be bordering on a neurosis.

We all sat around grinning rather stupidly, until Charlie relieved the tension, crossing and patting his wife’s shoulder.

“My dear Millie, you’re beginning to imagine things. You’ll be saying next that Polly was Seymour Alstone’s filly out of Mrs. Baines, and that the kidnappers are going to extort an enormous ransom from the old man.”

Millie grinned up at Charlie affectionately and seized the opportunity to snitch his drink.

“Far more likely the old son of a gun kidnapped her himself. Anyone that’s pulled as many fast ones in business as Seymour Alstone wouldn’t stop at kidnapping if he felt like it. I expect he’s got her locked up in one of those big empty rooms of his. Or maybe he’s eaten her. Our kids call him the Big Bad Wolf.”

Millie was quite herself again and launched on her favorite topic—one that was, incidentally, the favorite topic of the whole valley—the villainies, real or imaginary, of Seymour Alstone, the landlord from whom Toni and I rented our cottage. But we were not his only tenants. With a relentless determination to become “lord of the manor,” old Seymour had been slowly buying up all the property in the neighborhood. By now practically every estate had fallen into his rapacious clutches, and only the Goschens, with their four hundred acre farm, had managed to preserve a defiant independence.

“My dears!” Millie’s face was shining again, pink and seraphic. “I must tell you the latest. I took Mrs. Baines some eggs today and she was rabid about old Seymour—at least, as rabid as she dared be, poor soul, against her husband’s employer. Apparently, he’d caught her young Tommy trespassing on his flower beds last week and the old scalliwag lugged him round to the Baines’ cottage—personally, mind you—and wouldn’t leave until he’d had the kid whipped right there and then before his eyes. Mrs. Baines said he just stood and gloated. I think it’s positively indecent.”

“But the funny part of it was,” put in her husband with boyish glee, “that he sent Mark Baines out for a cane, and he came back with a split stick which made a hell of a noise but didn’t hurt.” He laughed. “Mark’s not such an idiot as we all make out. You’ve got to be pretty smart to fool old Seymour Alstone.

“Aye, he’s a hard man and just.” Toni was collecting the empty glasses, “But so long as he lets us hunt over his property, I don’t see that it matters what he does with his free time. If he wants to beat little children, God knows we’ve enough and to spare in the neighborhood.” He grinned at Millie. “Particularly if you and Mrs. Baines continue to keep up to schedule.”

Millie’s comeback was cut short by the arrival of Valerie. Valerie Middleton is the type of girl who immediately makes herself felt in a roomful of people. What exactly is the secret of her charm, I have never been able to discover. It is not that she is particularly beautiful, although her tip-tilted nose and broad, mischievous smile are a constant delight. It is not that she is witty or brilliant. Luckily she has never caught the contemporary knack of twisting everything into a wisecrack. Perhaps it is her basic honesty that makes her what she is—the honest freshness of her appearance; the honest forthrightness of her manner; and the utter lack of self-consciousness or hypocrisy in her approach to men and women alike.

And she could so easily have become otherwise, for life had given her a great deal of the rough and very little of the smooth. She lived in a small cottage with her mother on the Alstone estate, and the Middletons’ lapse into poverty had been almost as sensational as the Alstones’ rise to wealth. Valerie’s father, who had committed suicide some years ago, had been a brother of Mrs. Seymour Alstone, now long deceased, and had been connected with Seymour himself in a large steel firm just outside Rhodes. Rumor had it that old Alstone had sold the company’s stock short to his own brother-in-law and, in the collapse of 1929, had made a killing in more senses of the word than one. Whatever the truth of this report, it was a known fact that Valerie and her mother were now so crippled financially that they were obliged to live practically on the charity of the man who was supposed to have ruined them. Mrs. Middleton took it very hard, yet no one had ever heard Valerie say a malicious word against her uncle. But that was just like Valerie.

As she entered now, her pale blonde hair slightly tousled, (for she never wore a hat) her cheeks colored by the night air, it struck me for the hundredth time what a gorgeously eupeptic creature she was. It was a physical pleasure just to look at her after a day of pale sickly faces at the hospital.

She grinned at us and then ran out into the hall, returning with a small and very sulky Sealyham.

“Sorry about Sancho Panza,” she said, “but I had to bring him. If I leave him with Mother, they just get together and bark at everything.”

Toni brought her a drink and I watched her eyes smile into his.

“I’m late,” she said, sipping the highball. “I’ll have to hurry and catch up. No news on Polly, I suppose?”

We told her of Baines’ visit.

“It’s really awful. I feel so sorry for old Ma Baines. What do you think’s happened?”

“Millie’s just been saying your uncle ate her,” remarked Toni.

Valerie laughed. She has a cool, cl

ear laugh like a boy’s. “I expect he did. I’m really beginning to believe he is rather a wicked uncle. Mother’s been in one of her denunciatory moods. I’ve heard nothing but your Uncle Seymour this, your Uncle Seymour that, all day.”

I started to make some remark, but for the third time that evening we were interrupted. Outside there was the sound of a car stopping, followed by footsteps on the garden path. Our nerves must have been quite on edge by that time, because everyone looked apprehensively toward the door. Even Sancho Panza jumped up and then subsided, growling, behind Valerie’s chair.

It turned out to be two of our students from the hospital—Gerald Alstone, old Seymour’s grandson, and his friend, Peter Foote. As they entered they presented a violent contrast. Gerald was slight and meek. He always looked as though his childhood had been spent getting in the way of grown-ups who had no use for him. And now, in his twentieth year, he had a pathetic, unwanted air which, doubtless, was due to the fact that his mother and father had been divorced when he was very young. Although he did not wear spectacles, his eyes had a trick of peering myopically at random objects which had no significance in themselves. He was awkward in company.

Peter Foote, on the other hand, was rather handsome in an easy, graceful way. Being the son and heir of very rich parents somewhere in Illinois, friends and self-assurance came easily to him. Before embarking upon his medical career, he had been sent twice round the world by his indulgent mother and from his travels he had acquired that well-groomed sophistication which blossoms so often and so unexpectedly upon the emancipated middle westerner. Although erratic and wildly impractical at times, I had always found him most responsive as a student and Toni had said that he was the most brilliant and hardworking member of his pathology classes at Rhodes.

Neither of us could say the same for Gerald Alstone, who had great difficulty in making the grade. Even his grandfather’s money and threats looked as though they would not be sufficient to keep him at medical school another year if he did not make a better showing.

Death Goes to School

Death Goes to School Hunt in the Dark

Hunt in the Dark The Cases of Lieutenant Timothy Trant (Lost Classics)

The Cases of Lieutenant Timothy Trant (Lost Classics) Death for Dear Clara

Death for Dear Clara S.S. Murder

S.S. Murder Death and the Maiden

Death and the Maiden The Grindle Nightmare

The Grindle Nightmare Cottage Sinister

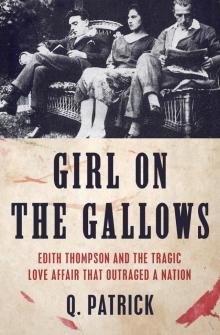

Cottage Sinister The Girl on the Gallows

The Girl on the Gallows