- Home

- Q. Patrick

Death for Dear Clara

Death for Dear Clara Read online

Death for Dear Clara

A Lieutenant Trant Mystery

Q. Patrick

I

The offices of the Van Heuten Literary Advice Bureau were soothingly feminine. Discreetly colorful fabrics curtained the wide expanse of window. Gay vases of flowers added that intimate touch which was the keynote of the business. For Mrs. Clara Van Heuten dealt with temperament and talent, and her clients required the most delicate of handling.

But of all the office’s appointments, Clara Van Heuten herself was the most effective. As she sat behind the golden chrysanthemums on her desk, briskly intent upon the pile of manuscripts in front of her, she seemed the very essence of understanding and sympathy. The fashionable whiteness of her hair together with the mature wisdom of her eyes managed to combine motherliness and modernity. A woman of tact and a woman of breeding; at fifty, Mrs. Van Heuten looked exactly what she was—a monument to the surprising success of a society woman who had been obliged to go into business at an age when most business people were thinking of retiring.

“Not exactly a literary agent, my dear,” she was in the habit of explaining. “Nothing practical or commercially useful, I’m afraid. It’s just that I want to be helpful—to guide those who have the urge, the inspiration to write.”

And that is what she had told her many society friends five years before when a sudden and unexpectedly penurious widowhood had forced upon poor dear Clara the alternatives of elegant dependence or hard-working independence. Everyone had admired her courage in starting the Literary Advice Bureau. They had sent her their own literary efforts. Clara Van Heuten was so sympathetic, so encouraging—and then, she charged such absurdly small reading fees. How could she do it?

But she had done it. And now, one glance at the expensively modernistic office, one glance at Clara Van Heuten’s perfectly cut Schiaparelli model were sufficient to prove that she had risen, like a middle-aged phoenix, from the ashes of financial ruin. As before her widowhood, her Park Avenue apartment was the place where Society met the Intelligentsia and—actually liked it. Her sympathies were as wide as her capacity for entertaining. There were many who would have claimed that Clara Van Heuten was one of the most appreciative and the most appreciated women in New York.

Certainly it would have seemed incredible that anyone could dislike this distinguished, white-headed woman who sat working at her desk beside the clustered blossoms of the chrysanthemums. It was incredible that she should be capable of raising any violent emotions.

And yet, she was violently concerned in the emotional lives of nine widely diversified people who, even now, were converging like inexorable forces toward the pivotal point of her office. Nine people—each one of whom was potentially her murderer.

Clara Van Heuten glanced at her tiny platinum wrist-watch. Twelve-thirty. As she rose to her feet, with pleasant thoughts of lunch, she let her gaze travel over the golden chrysanthemums. Idly, she picked up her steel paper-knife and cut off a wilted bloom.

Her eyes were tranquil, undisturbed.…

At the same moment, the same tranquil eyes were staring out from a slightly tarnished silver frame, held in the hand of another, much younger, woman. The Princess Walonska sat in the long morning-room of her house on Sutton Place, staring at the photograph’s inscription.

“For dear Patricia and Dmitri—Clara Van Heuten.”

A single chime from the clock on the mantel distracted Patricia Walonska’s attention. Slowly she set the photograph down on a table whose highly polished surface was partially obscured by four new briefcases.

Twelve-thirty—her guests would be arriving at any moment now.

The Princess rose to her feet, a slim, streamlined figure dressed in very simple, very expensive black. With studied dignity, she moved across the room to an inlaid ebony chest.

Patricia Walonska had been a princess for less than six months, but already she had acquired a regal bearing worthy of Marie Antoinette and an imminent guillotine. Patricia Walonska, née Cheney, never did things by halves.

In 1929, she had been the New York débutante to end all débutantes. Her wild escapades had run neck and neck on the front pages with the downward careening of stock prices. While Manhattan’s other playgirls melted away like their parents’ margins, Pat Cheney had ridden the deluge with orchids flying. Literally, for on one occasion she had chartered an airplane and bombarded Fifth Avenue with a shower of hot-house flowers.

But flaming youth had palled. When the Cheneys began shrewdly to switch their powerful political influence to the Democratic party, Patricia had abandoned her capitalistic pranks to become the democrat to end all democrats. She had deflected her money and her boundless energy into soup for soup kitchens and butter for breadlines. She had become at once the champion and the terror of Manhattan’s unemployed.

Recently, just when the so-called return to prosperity had left her no alternative but communism, Patricia had met and married the expatriate Prince Dmitri Walonski. That authentic if impoverished gentleman had converted her from red to white. Now, society’s most versatile of chameleons was proving to a breathless world that she could be the princess to end all princesses.

As she paused before the chest, it would have been impossible to detect in her any lingering traces of her cast-off personalities. And yet, at this particular moment, Patricia was planning the wildest, the most determined and possibly the most dangerous scheme of her career.

Deliberately she pulled open a drawer to disclose four small revolvers.

In hands that were perfectly steady, she carried them to the table and slipped one into each of the four briefcases. As she pressed a button to summon the butler, her eyes rested for a long moment on the photograph of Clara Van Heuten.

“You’d better make the cocktails now, William. Old-fashioneds. My guests will be needing something strong.” A shadow of the old reckless smile gleamed in Patricia’s eyes. “And the frame of this photograph is tarnished. You can bring it back with the tray.”

Several minutes later the sound of a bell, ringing in the distant hall, broke the silence of the room. Patricia Walonska glanced at the four briefcases; her lips tightened. She was ready to receive her first guest.

“Miss Gilda Dawn.”

The butler’s voice from the door was reverential. He paused just a fraction too long for decorum to watch in fascination while Hollywood’s most flood-lighted figure swept into the room.

Superb, synthetic, be-sabled, Gilda Dawn extended a gloved hand to her hostess and crooned:

“Princess, this is delightful. Of course, my personal appearance engagement at the Music Hall has left me too terribly exhausted, but…”

The instant after the door had closed behind the Great Public in the person of the butler, the screen’s ranking Lotus Lady gripped Patricia’s arm and asked hoarsely:

“What’s the big idea about that telegram you sent? It scared me stiff. What’ve you found out?”

“I think we’d better wait until all my guests have come,” murmured Patricia.

Despite the sensational coiffure (once ebony, then flame, currently blondette), despite the twenty-five dollar silk stockings which sheathed the two hundred and fifty thousand dollar legs, Gilda Dawn had obviously reverted to the suspicious Iowa farm girl who had early learned all women were her enemies.

“It isn’t just a gag?” she persisted. “Seeing I’m to play Mary Magdalene in the Fall, they stuck me with a moral turp clause in my new contract and I’m half way through a divorce as it is. So if you’ve dug up any dirt, I’m going to get my manager, Mr. Schneider, over here right away.”

Patricia smiled wryly. “I’m afraid we’ll have to keep even Mr. Schneider out of this. It’s a little matter which you and I and tw

o other women have to work out for ourselves.”

There was a flat moment of silence, then brisk footsteps sounded in the corridor outside.

“I expect that’s Miss Kennet,” said Patricia. “You know her, I think.”

“Bea Kennet, the writer?” Gilda Dawn’s scarlet-nailed fingers jabbed a cigarette into a long jade holder. “You don’t mean that god-awful woman’s mixed up in this?” Then, as though remembering her dignity, she added sweetly: “Oh, yes, I know Bea Kennet well. She did a couple of vehicles for me in Hollywood.”

“The poor hack who hitched her vehicle to a star.”

Gilda Dawn turned as the derisive voice from the door continued:

“In your case, Lotus Lady, the female dog star.”

Beatrice Kennet, author of a score or more of slickly adulterous magazine serials, pushed past the butler and strode into the room. In tailored tweeds and a shirt and tie which just stopped short of the masculine, she typified dividend-paying Bohemianism. Her hands were thrust in her pockets; her close-cropped hair framed the impudent features of an over-sophisticated boy.

“Morning, Pat Cheney. Haven’t seen you since you acquired that Slavic moniker. Do I kiss your hand or call you Comrade? And what the hell’s the point of your lurid telegram? I dropped everything and dashed over here all strung-up for some really juicy copy.”

“You’ll get it,” said Patricia grimly.

The butler had replaced the now gleamingly framed photograph of Clara Van Heuten. He set down the tray of cocktails and withdrew.

Bea Kennet snatched a glass.

“Old-fashioneds backed by the divine Clara Van Heuten! Most appropriate!” She tilted the drink to her lips. “Well, here’s to the death of an afternoon.”

Gilda Dawn had sunk languorously into a chair, but her eyes were still watching Patricia. “Well,” she asked, “now Miss Kennet’s come, aren’t you going to give us the pay-off on that wire?”

“Exactly.” Beatrice Kennet had pulled a crumpled envelope from her pocket. Her capable fingers were almost imperceptibly unsteady as they tugged out the telegram. She read:

HAVE DISCOVERED SOMETHING OF VITAL IMPORTANCE TO YOU STOP MAY LITERALLY BE MATTER OF LIFE AND DEATH STOP COME TWELVE-THIRTY TODAY

Her keen black eyes regarded Patricia alertly. “Is this just a throwback to the dangerous deb era? Or are our valuable lives really blighted?”

“There is still one more guest,” repeated the Princess almost mechanically. “I think we’d better wait for her.”

She had crossed to the table and was fingering one of the briefcases. There was something disquieting in her level gray eyes. They had a deflating effect even upon Beatrice Kennet.

Neither she nor the Lotus Lady spoke again. The author’s second old-fashioned glass clattered empty on a coffee-table. Gilda Dawn’s long cigarette holder beat a nervous tattoo against an ash tray.

They both started when the door opened for the third time.

“Mrs. John Hobart.”

A girl stood on the threshold. She was very young, with auburn curls and ingenuous eyes. She moved forward a trifle breathlessly.

“Oh, Princess, I came just as soon as I got your telegram.” There was the slightest trace of a lisp.

Susan Hobart had inherited seventeen million dollars from her uncle, Daniel Stuckey, the Ohio Bone King. But wealth had done nothing to alter the almost exaggerated simplicity of this small town Cinderella.

“If you’ve come all the way from Ohio, Mrs. Hobart, I expect you—”

Patricia had crossed to the bell, but Susan Hobart hurried after her, clutching her arm.

“Wait a moment. There’s something I’ve got to tell you. I’ve guessed. That’s why I came—to stop you doing anything crazy.”

Her blue eyes settled on the photograph of Clara Van Heuten.

“So I was right,” she breathed. “I do know what you’ve found out. Princess, you mustn’t, you can’t do anything to…”

“For God’s sake give the girl a cocktail,” broke in Beatrice Kennet waspishly. “She gets on my nerves.”

Susan Hobart wheeled round, staring as if she were seeing her fellow guests for the first time.

“So these ladies, too…!”

“Yes. We are all four of us in it up to the neck.” Patricia Walonska gave an odd smile. “Even if you have guessed what I am going to say, Mrs. Hobart, I’m sure you’ll agree with me that dangerous diseases call for dangerous remedies.”

In the brief moment of silence that followed, those four women, grouped almost theatrically in the center of the room, made an astonishing contrast. Each one of them was young, rich, attractive. Each one of them set Winchell’s typewriter clicking whenever she patronized a new dressmaker, a new lover, a new nightclub or a new husband. And yet, despite their news value, these four women, from such utterly different spheres of life, seemed to have nothing in common except their present proximity and their ill-concealed uneasiness.

“There is something,” said Patricia slowly, “which has to be done. I think you three women have enough common sense to realize that we are the people who’ve got to do it.”

No one spoke. There was a tension in the long room like a delicate wire stretched taut in a trap about to be sprung. The Princess had picked up one of the briefcases again and was fingering the zipper.

“You can’t mean that!” The words came in a little gasp from Susan Hobart. She was pointing at the briefcase. Its unfastened zipper had revealed the gleaming barrel of a revolver. “Princess, you can’t expect us to do that.”

Her eyes, dilated with panic, turned once again to the tranquil photograph in its silver frame. “Tell me,” she breathed, “is she coming here?”

“No.” Patricia was smiling again, and her smile was dangerous. “But the four of us are going to visit her this afternoon. We’re going to visit the cleverest and, probably, the most unspeakable woman in New York, our very dear friend Clara Van Heuten.”

“Mrs. Clara Van Heuten is at lunch. Who’s calling, please?”

“Oh, this is Derek Muir. I have a note of introduction from a mutual friend. I was wondering whether Mrs. Van Heuten could see me this afternoon.”

A brief pause from the other end of the telephone; then the secretary’s voice again, brisk, curt:

“Around three-thirty?”

“Good. Excellent.”

The young man laid down the receiver and lounged back on his uncertainly springed bed. As he gazed around the small, dreary room, his lips moved in a smile of indolent satisfaction.

It was almost one o’clock, but Derek Muir had not bothered to get up. What was there about a morning to be worth getting up for? Breakfast…? Breakfast suggested money and money suggested work. Derek Muir had been a stranger to both money and work ever since he came East two months before. Life was an impecunious blank.

But the thought of his appointment that afternoon did something to dispel his languor. Slipping off his faded yet still flamboyant pajamas, he crossed to a rickety dressing-table, slabbed with morgue-like marble.

The pitted woodwork around the glass was adorned with effusively inscribed photographs of banal, near-beautiful blondes. But Derek Muir was hardly aware of these tokens of feminine admiration; he was rapt in narcissistic concentration of the face which would always be more attractive to him than any other. And even that mercury-scarred mirror could not detract from its just too perfect features. Derek Muir contemplated himself with satisfaction. In a crude, unappreciative world, self-admiration was the only luxury that cost him nothing.

But today it was not the only luxury in his possession. Derek Muir turned from his own reflection to gaze at his latest acquisitions. They were spread on a chair of despairing plush, neatly folded, just as he had taken them from their various boxes. A smoke-blue suit, a Bond Street shirt and tie and some seductively patterned socks. At the foot of the chair, nestling gray and soft like a pair of twin doves, was the latest offering in suède shoes.

Dere

k Muir was justly proud of his new outfit. He had paid, or rather promised to pay, almost two hundred dollars for it. It was designed to dazzle femininity in general, and in particular, the unknown Mrs. Van Heuten.

Lovingly, almost with reverence, he started to dress, fingering each garment as though it were some fragile ornament which the least roughness might shatter. When he regarded the final effect in the mirror, Derek Muir forgot for a moment the sordid reality of rent long overdue, inadequate meals in automats and the enforced squalor of his frugal loneliness. He let his imagination roam into the tentative future.

There, he saw himself owning not one but dozens of devastating suits; he saw himself sauntering triumphantly along the Côte d’Azur, leaving broken banks and broken hearts in his wake. He saw gleaming limousines, soft-footed valets, house-parties encrusted with celebrities who hung enraptured on the world-weary epigrams which fell with such splendid casualness from his lips.…

All these dreams might, perhaps, be circumscribed in that grimy little piece of pasteboard, propped against the mirror—Dane Tolfrey’s card with a note scrawled alcoholically on the other side.

Idly Derek Muir picked it up and turned it over. There, staring up at him tantalizingly, was written the name and address of the woman who might work miracles.

“Clara Van Heuten,

Literary Advice Bureau

To introduce Mr. Derek Muir

A Very Accomplished Killer.”

Derek Muir glanced at the cheap tin clock on the dressing-table. Twenty past one. There was still plenty of time before his appointment. He slipped the card into his pocket and strolled down the hall. His movements were casual yet furtive. He was anxious not to draw to his resplendent new outfit the attention of a rent-hungry landlady.

Successfully gaining the street, he walked with a briskness of purpose. He wanted to see Dane Tolfrey once again before the interview with the mysterious Mrs. Van Heuten. And he had a very shrewd idea where Tolfrey was to be found.

He was right. When he entered the bar of the Longval, Dane Tolfrey was almost the sole occupant, perched on his usual stool. The last of the long line of short-lived Tolfreys had just finished his fourth double brandy and was about to inflict an unwise fifth on a fast cirrhosing liver.

Death Goes to School

Death Goes to School Hunt in the Dark

Hunt in the Dark The Cases of Lieutenant Timothy Trant (Lost Classics)

The Cases of Lieutenant Timothy Trant (Lost Classics) Death for Dear Clara

Death for Dear Clara S.S. Murder

S.S. Murder Death and the Maiden

Death and the Maiden The Grindle Nightmare

The Grindle Nightmare Cottage Sinister

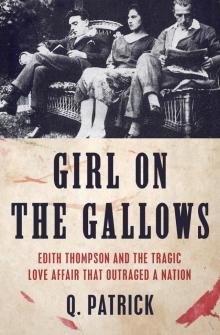

Cottage Sinister The Girl on the Gallows

The Girl on the Gallows