- Home

- Q. Patrick

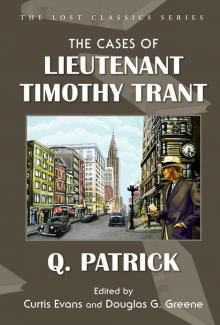

The Cases of Lieutenant Timothy Trant (Lost Classics)

The Cases of Lieutenant Timothy Trant (Lost Classics) Read online

The Cases of Lieutenant Timothy Trant

By Q Patrick

Q. Patrick/Patrick Quentin

(Richard Webb and Hugh Wheeler

and their Scottish Terrier, Roddy)

Photograph taken ca. 1939–1940; From the Hugh Wheeler

Collection, Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center at Boston University

Copyright © 2019

by Crippen & Landru Publishers, Inc.

Published by arrangement with the estate of Hugh Wheeler Cover artwork by Gail Cross

Lost Classics logo, adapted from a drawing by Ike Morgan, ca. 1895

FIRST EDITION

ISBN (cloth edition): 978-1-936363-32-2

ISBN (trade softcover): 978-1-936363-30-8

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free, recycled paper

Crippen & Landru Publishers

P.O. Box 532057

Cincinnati, OH 45253

USA

Jeffrey A. Marks, Publisher

Douglas G. Greene, Senior Editor

e-mail: [email protected]

web: www.crippenlandru.com

Contents

Introduction – by Curtis Evans 7

Detective Who’s Who 15

She Wrote Finis 17

White Carnations 88

The Plaster Cat 106

The Corpse in the Closet 130

Farewell Performance 143

The Wrong Envelope 156

Murder in One Scene 213

Town Blonde, Country Blonde 225

Who Killed the Mermaid? 230

Woman of Ice 236

Death and Canasta 247

Death on Saturday Night 252

Death on the Riviera 258

Girl Overboard 264

This Looks Like Murder 275

Death Before Breakfast 279

Death at the Fair 284

The Glamorous Opening 290

Murder in the Alps 296

On the Day of the Rose Show 307

Going … Going … Gone! 314

Lioness vs. Panther 320

Sources 329

Introduction: Trant Intervenes

The Lieutenant Timothy Trant Short Crime Fiction of Richard Wilson Webb and Hugh Callingham Wheeler

Over a half-century ago, in 1962, there appeared the only collection of Q. Patrick/Patrick Quentin short fiction published in English during the lifetimes of Anglo-American crime writers Richard “Rickie” Wilson Webb (1901–1966) and Hugh Callingham Wheeler (1912-1987), the two primary creative forces behind these alliterative pseudonyms. Several years earlier, New York Times book reviewer Anthony Boucher, then dean of American mystery critics, had “pleaded” (his word) in one of his columns for the publication of a collection of the short suspense fiction of the two men. This plea was met, much to Boucher’s approbation, with the publication of the Edgar Award winning The Ordeal of Mrs. Snow and Other Stories, which gathered such superbly sinister pieces as “Portrait of a Murderer,”

“Mother, May I Go out to Swim?”

“Thou Lord Seest Me” and “Love Comes to Miss Lucy”— spiritual predecessors, if you will, of the lauded short fiction of modern-day Crime Queens Ruth Rendell and P. D. James. Yet even as he effusively welcomed these twisty tales of deathly doings, Boucher made yet another plea to the publishing gods: that a companion volume of Webb and Wheeler’s “equally skilled pure detective stories” be delivered as well unto the faithful mystery reading multitude.

Now, fifty-six years later, Anthony Boucher’s prayer finally has been answered by those consummate deliverers at Crippen & Landru, with the publication of The Cases of Lieutenant Timothy Trant, a volume which collects Rickie Webb’s and Hugh Wheeler’s twenty-two short works about the murder investigations of police detective Lieutenant Timothy Trant, the sleuth in seven masterful Q. Patrick and Patrick Quentin detective novels and one Crime File. The appearance of The Cases of Lieutenant Timothy Trant today, on the eve of the centenary of the dawning of the Golden Age of detective fiction, seems most appropriate, for the book constitutes a wickedly good gathering of scrupulously “fair play” murder puzzles, the sort of blue-ribbon brainteasers that twenty-first century counterparts of classic crime fiction connoisseurs like the late Anthony Boucher continue to crave.

* * *

It was during the summer of 1933 that twenty-one-year-old Hugh Wheeler, a prodigiously talented recent graduate of University College London, met and struck it off in the City with visiting native Englishman Rickie Webb, a thirty-two-year-old Philadelphia pharmaceutical executive and author of four “Q. Patrick” detective novels. In August young Wheeler moved with Webb to Philadelphia, where the two men began crafting a crime writing career together. This career very much included the publication of short fiction as well as novels, Webb having concluded, as he put it in a letter that year to Wheeler’s parents, that the “popular American market” was “a little gold mine.” Although 1934 was a fallow year for the pair, with not a single known work of fiction by them, long or short, appearing in print, the period from 1935 to 1937 saw the publication of no less than seventeen pieces of fiction—six hardcover novels and eleven serialized novels and novellas—co-written by the two men under three pseudonyms, Webb’s original “Q. Patrick” and the newly launched “Patrick Quentin” and “Jonathan Stagge.” This was an impressive rate of production even by the elevated standards of the mystery genre in the Golden Age, when some of the era’s most adept masters of the detective fiction form were known to churn out four or more works annually. Yet more impressive is the consistent high quality of Webb and Wheeler’s detective fiction.

Initially the pair lucratively tapped diverse markets for their work in Street & Smith’s Detective Story Magazine, one of America’s premier purveyors of “pulp” crime fiction (so named for its cheap pages made from wood pulp), which aimed primarily at a male audience, and in The American Magazine, a so-called “slick” (so named on account of its more expensive, glossy paper) with a readership composed to a great extent of middle-class women. Some of the more notable work of crime fiction the two men published in these magazines at this time were “The Frightened Landlady,” a novella detailing a gruesome case for Dr. Hugh Cavendish Westlake, the lead series character in their Jonathan Stagge novels, “The Hated Woman,” described by Bill Pronzini as a “dark character study and murder tale,” and the thrilling romantic mysteries “The Jack of Diamonds,”

“Exit Before Midnight,” and “Another Man’s Poison.” (All of these titles, it is hoped, will be reprinted in a future Crippen & Landru volume.)

During the 1940s Rickie Webb and Hugh Wheeler continued to write for both the pulps and the slicks. There were short story publications in Doc Savage and The Shadow, while that dashing if disputatious mystery-solving couple Peter and Iris Duluth, lead series characters in Webb and Wheeler’s highly acclaimed Patrick Quentin novels, appeared in the glossily illustrated pages of The American Magazine in 1941, where they solved colorful crimes in the novelettes “Death Rides the Ski-Tow” and “Murder with Flowers” (both of which are included in the 2016 Crippen & Landru volume The Puzzles of Peter Duluth). Similarly, New York police detective Lieutenant Timothy Trant, Webb and Wheeler’s posh, grey-eyed sleuth in the novels Death for Dear Clara (1937), Death and the Maiden (1938), and the Crime File, The File on Claudia Cragge (1938, actually a collection of clues for the reader to solve), made his short fiction debut in December 1940-January 1941, in the Canadian slick Maclean’s.

The Maclean’s story, a novella entitled “She Wrote Finis,” was the first of twenty-two Timothy Trant murder tales that wer

e published over the next fifteen years. After a four-year lapse (during which time Wheeler saw service in the U. S. Army Medical Corps at Fort Dix, New Jersey and Rickie Webb in the Red Cross in Hollandia, Indonesia), there next came, in the American slick Collier’s in February 1945, “White Carnations.” In the United States, the rest of the Lieutenant Trant stories appeared, with one apparent exception, in smaller, digest-sized magazines, two of them, “The Plaster Cat” and “The Wrong Envelope,” in the highly-praised but short-lived Mystery Book Magazine, and seventeen in the Frederic Dannay edited Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, the most important American forum for quality crime fiction in existence after the Second World War. (However, the seventeen EQMM stories were originally published in This Week, a Sunday newspaper supplement that was carried around the country, and yet another Trant tale, “Death at the Fair,” was only recently discovered by mystery genre expert Tony Medawar in the British newspaper the Evening Standard; it is included in this volume.) From 1946 to 1955, Q. Patrick, under whose name almost all of the Webb and Wheeler short fiction was published, became one of the mainstays of EQMM and his short stories were the recipients of multiple Queen’s Awards. The acclaim these stories received was merited, for both the Webb and Wheeler suspense fiction and the Lieutenant Trant detective stories are models of their respective types. From his debut in the novel Death for Dear Clara (1937), it is clear that Timothy Tregaskis Trant—”the smoothie of the Homicide Squad” and its “specialist in high-life slayings”—belongs to the swanky ranks of the new breed of handsome, well-born and well-bred policemen who had insouciantly infiltrated the pages of Thirties detective fiction, where such police sleuths as Ngaio Marsh’s Roderick Alleyn, Michael Innes’ John Appleby, Henry Wade’s John Poole, E. R. Punshon’s Bobby Owen and John Rhode’s Jimmy Waghorn were bidding fair to take the clue-finding field back from amateur swells like E. C. Bentley’s Philip Trent (whose surname possibly provided Webb and Wheeler with the inspiration for Trant), Dorothy L. Sayers’ Lord Peter Wimsey, Margery Allingham’s AlbertCampion, Miles Burton’s Desmond Merrion, S. S. Van Dine’s Philo Vance and Frederic Dannay’s and Manfred Lee’s Ellery Queen. In biographical information, included in this volume, which Webb and Wheeler provided for the Anthony Boucher edited mystery anthology Four-and Twenty Bloodhounds (1950), we learn that Trant, born in 1914, attended East Kent School and Princeton University, from where he graduated in 1935, idiosyncratically entering the New York Police Force the same year. Ceding no ground to toffs like Lord Peter and Philo Vance, Trant’s hobbies are collecting neckties and Italian art, while his peculiarities are “sartorial elegance” and a “fondness for murderesses.” One can discern, as well, considerable resemblance to Trant in Hugh Wheeler himself.

Lieutenant Trant encounters murderesses and murderers alike in the twenty-two shorter criminal cases so enjoyably chronicled by Q. Patrick, all of which are fine examples of this more diminutive yet equally deadly detective fiction form, from the longer pieces to the shorter shorts. Individual readers will find their own favorites among them, but mine certainly include both of the longer works, which are the cleverly clued novella “She Wrote Finis,” wherein Lieutenant Trant seeks the creative killer of ambitious and unscrupulous aspiring novelist Minna Lucas (she shares the surname of Rickie Webb’s mother) among her “closet friends” in the literary, acting and art worlds, all of whom hated her; and the novelette “The Wrong Envelope,” a superb exercise in screw-tightening feminine tension of Mignon Eberhart proportions, wherein a misplaced missive and a fiendish murder create ample anxiety for Kate Laurence, a beautiful and wealthy orphan, on the eve or her marriage, before Lieutenant Trant comes to her rescue.

As for the shorter tales, they offer impressive examples of Hugh Wheeler’s witty writing and his and Rickie Webb’s clever clueing. All of them are sweet delight for devotees of detection, but some particular highlights in my view are “White Carnations,” wherein Lieutenant Trant is prevailed upon by lovely Angela Forrest, a Princeton dance partner from nine years earlier, to investigate the dire menace to her family and herself symbolized by birthday gifts of white carnations; “The Plaster Cat,” wherein Trant investigates the suspicious death of Madeline Winters at the prestigious Ruskin School for Girls; “The Corpse in the Closet,” which introduces Trant’s amusingly overbearing sister Freda (probably named for Webb’s own favorite sister); “Who Killed the Mermaid?,” which sees Trant’s aesthetic penchant for neckties come into play when a train passenger is strangled with his own hideous tie; “Woman of Ice,” wherein Trant encounters death in Venice; “Death on a Saturday Night,” in which matinee idol Tyrone Power (“the words Tyrone Power, like a magic incantation, still loomed on the darkened marquee”) provides a key clue in a murder in New Hampshire, where Trant has gone for a skiing holiday; “Girl Overboard,” an ingenious shipboard mystery, originally published in Four-and-Twenty Bloodhounds (where editor Anthony Boucher pronounced it “one of Trant’s deftest cases”), with all-too plausible modern-day resonance; “This Looks Like Murder,” in which the melodious strains of a Strauss waltz inspire Trant in his hunt for a killer; “Death before Breakfast” and “Death at the Fair,” which respectively debut Freda’s pet dachshund, Minnie, and her son, Colvin, both of them equally demanding of Trant; “On the Day of the Rose Show” and “Going... Going... Gone!,” wherein Trant meets murder at a Connecticut country house and at an antiques auction; and the final piece of Trant short fiction, “Lioness vs. Panther,” which pits two diva actresses against each other when the actor playing the bit role of the butler has the nerve to get himself poisoned—for real—onstage.

Like most creative and prolific writers, Webb and Wheeler sometimes reused plot devices, for example, the mis-sent envelopes in “The Wrong Envelope” and “Murder in One Scene.” (Readers will surely find other instances). The most obvious example has a different origin. After the anxious editor of This Week fretted that the shipboard murder in “Girl Overboard” recalled a real-life slaying, Hugh Wheeler at the editor’s behest changed the setting from an ocean liner to an Alpine chalet, with a corresponding change of clues. Readers interested in judging the creativity that went into this should see the altered version of the story, “Murder in the Alps,” included in this volume.

In the Timothy Trant tales readers will find creative clueing galore as they travel with the intrepid sleuth though sophisticated New York society and acting circles, New England country weekend getaways, and even, on a couple of occasions, Europe (Venice and the Riviera). All of these locales were familiar to the authors themselves, who during the time when most of the Trant stories were published resided in New York City and the Berkshire Hills of Massachusetts, making annual pleasure excursions to Europe, the Caribbean and Latin America. Readers may be wowed by the assorted drop dead gorgeous women and devilishly handsome men, many of them up to no good, whom they will encounter in these privileged places, but Trant himself remains unfazed by the rich and famous as he collars killer after conniving killer. It is regrettable that Trant’s shorter adventures in murder ended, like those of Peter Duluth, in 1955, not long after Rickie Webb and Hugh Wheeler permanently parted ways from each other in 1952, but what a rich legacy of ingenious mid-century murder the two accomplished authors have left us. Happily their crime fiction, long and short, finally is returning from the wings after far too long an absence from the mystery stage.

— Curtis Evans

Detective Who’s Who

TRANT, Timothy Tregaskis, police officer; b. 1914; s.

T. R., M.D., and Ellen (Tregaskis) T.; Educ.: East Kent School; Princeton University, Phi Beta Kappa, Class 1935. Entered

N. Y. Police Force, Homicide Division, 1935. Hobbies: Italian art; collecting neckties. Peculiarities: Sartorial elegance; fondness for murderesses. Most famous cases (chronicled by Q. Patrick): Death for Dear Clara (1937); Death and the Maiden (1939). Less complicated cases, chronicled briefly as “White Carnations” (1944); “Footlights and Murder” (1947); “Murder i

n One Scene” (1948); “Who Killed the Mermaid?” (1949); “Laura, Woman of Ice” (1949); several others.

She Wrote Finis

As the door of her office opened, Leslie Cole looked up from the manuscript she had been reading and blinked

at her visitor over impressive horn-rimmed spectacles. She blinked partly because she was short-sighted, but largely because there was something about Robert Boyer that dazed her slightly every time she saw him. He was so breathtakingly big, so masculine, so windswept, so exactly what he should be as a successful author of the great Canadian outdoors.

“Hi, bookworm.” He grinned at her, showing enviable teeth. “Ready for Minna’s party?”

The thought of Minna Lucas, which had been buried under manuscripts all afternoon, rose up unpleasantly. Leslie consulted her wrist watch.

“Quarter of six. I didn’t know it was so late.”

She disappeared through a door and returned almost immediately minus the spectacles and plus a tricky hat and a Persian lamb coat. She looked like a little girl masquerading as a grownup—a very pretty, rather helpless little girl who would inevitably gravitate toward a male shoulder in a crisis. No one would have guessed she was Morton and Bidlake’s toughest and shrewdest editor, the Leslie P. Cole who had discovered Robert Boyer’s The Story of Mark and boosted it into the biggest selling and most important first novel of a decade.

Death Goes to School

Death Goes to School Hunt in the Dark

Hunt in the Dark The Cases of Lieutenant Timothy Trant (Lost Classics)

The Cases of Lieutenant Timothy Trant (Lost Classics) Death for Dear Clara

Death for Dear Clara S.S. Murder

S.S. Murder Death and the Maiden

Death and the Maiden The Grindle Nightmare

The Grindle Nightmare Cottage Sinister

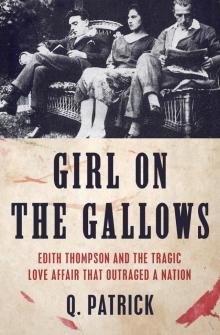

Cottage Sinister The Girl on the Gallows

The Girl on the Gallows