- Home

- Q. Patrick

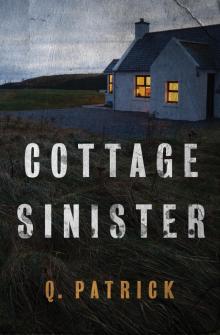

Cottage Sinister

Cottage Sinister Read online

Cottage Sinister

Q. Patrick

I

In a pleasant Somersetshire valley, about half way between the Mendip and the Quantock Hills, lies the village of Crosby-Stourton. Until the summer of 1930, when a series of terrible tragedies placed the name of the village upon the front page of every newspaper in England, it was a quiet, self-possessed little place. As it lay somewhat off the main road that runs between Bridgewater and Bristol, it had not yet been discovered by the American tourist or the marauding automobile, and its rustic charm was still unspoilt by the flamboyant road-signs and advertisements which are assiduously defaming the English country-side in their attempt to inflict unwanted goods on an unwanting public. An occasional enthusiast would come down to rub the brasses in its fine old Norman Church—an artist might sometimes have been seen, sitting in the Butter Market, skeching Crosby Cross, weather-beaten relic of some forgotten victory—but dissipations even of this humble kind were rare. Preoccupied with its own affairs, the village went serenely on—“the world forgetting, by the world forgot.”

Crosby-Stourton lay quietly dreaming of the past while a late June day in 1930 drew towards a close, suggesting in no way the tragedies which were to follow and were to make that peaceful spot into a Mecca for prurient sensation seekers from all over the country. A fading sunlight filtered through the rose-covered windows of the prettiest cottage of the village, touching old Mrs. Lubbock’s soft grey hair as she busied herself behind a large teapot. High tea was in progress, and the quantity and quality of the provision did not belie the fact that a welcome was taking place, a mother’s loving welcome to her two older daughters—Isabel and Amy—who had just arrived from London on one of their rare visits to their home. Both of them held superior positions in town as lady’s maids.

“Why, mother,” said Isabel, the older girl, as she looked eagerly round at the good things before her, “if I eat all that’s on the table, I declare I’ll be as stout as my lady.” Her eyes dropped to her spare, angular figure.

“You could do with a little more flesh, dearie,” replied her mother. “And I was thinking the same when I saw you in town last month. Ah, dearie me, but town is a long way away. If only your poor aunt were not so poorly, and could come down to see me here! It’s getting to be too long a trip for my old bones. But it’s God’s will and we mustn’t complain…. Let’s wait a few minutes for the tea in case our Lucy comes in. She’s been so anxious to see you!”

The two sisters, town clad and travel-stained, turned their chairs so as to look out of the window across the meadows towards the park and the great hall.

Their cottage, which stood a little way back from the road on the outskirts of the Crosby Estate, was known as Lady’s Bower, but is now more generally known as Cottage Sinister—for obvious reasons! It was, in itself, a miniature architectural gem, and cunning hands had added to its charms by a setting of rambler roses, Virginia creeper, larkspur and nasturtiums. It has been the cynosure—and perhaps the envy—of all discerning eyes, and to be allowed to live in it was considered the crowning favor that the Crosbys, the great family in Crosby-Stourton, had it in their power to bestow.

Crosby Hall, across the park from Lady’s Bower, was a fine old pile, grey with moss and hoary with recollections. It remembered the times when warriors rode out of its courtyard to fight as Crusaders in the Holy Land. During the Wars of the Roses it saw many a skirmish between the opposing forces, and a number of its villagers laid down their lives for the Lancastrian cause. Even to-day the ancients of Crosby-Stourton will entertain a casual stranger with the well-worn tale of Sir Marmaduke Crosby, last and most faithful of the Cavaliers, who barricaded himself in his own home and held at bay for many days a large body of Roundheads. Ever the centre of illustrious but lost causes, Crosby-Stourton heard the drums of Monmouth as they summoned her sturdy rustics to fruitless insurrection against the trained soldiers of James II. But after the 17th century it passed into oblivion, under the more prosaic rule of the House of Hanover. True, Wordsworth walked over one day from Nether-Stowey and wrote a rather poor sonnet in praise of its “historic stones and slumbrous living dead,” but he soon passed on and wrote better sonnets elsewhere.

Crosby-Stourton was now enjoying an era of comparative peace and prosperity. Sir Howard Crosby, eleventh baronet, was a good landlord if somewhat severe and unbending. While there was nothing of the dashing Sir Marmaduke about him, he gave his tenants few grounds for complaint and less for gossip. As for the present Lady Crosby, she was so plain in face and manners that she was often pitied more than those objects of charity on whom she lavished her great wealth and still greater generosity. Their only son, Christopher, the young squire and future baronet, was indeed remarkable in that he spent a great deal of time and effort in studying medicine in London, and that, in the words of the villagers, “he do talk to us poor folk as though he were nob-but a plain village lad and not one of the gentry at all.” Nevertheless, though the Hall was still the hereditary topic of conversation, the doings of the “quality” were not much more interesting to the natives than those of old Mrs. Lubbock and her pretty daughter Lucy, who were at least distinguished by living in the most charming cottage in the village.

Yet these distinctions had not brought Mrs. Lubbock the affection and respect from her fellow villagers which might have been hoped for in her declining years. No one indeed could deny that she had earned her right to spend the evening of her life in peace and tranquility, least of all Lady Crosby herself, in the service of whose family she had been faithful and diligent for over twenty years. No modern servant would have borne so patiently the whims and tantrums of Lady Crosby’s old invalid mother. No trained nurse could have done so much to make comfortable the last few years of that embittered and autocratic old lady whose tyrannical nature must often have tried the serenest of tempers.

But Mrs. Lubbock had been faithful to the last, and now two years had passed since death had released her charge from a miserable existence. Perhaps it had been lucky for Mrs. Lubbock that the old lady’s large fortune had been inherited, not by her dissolute son, George Burwell, but by her only daughter, Cynthia, who, as Lady Crosby of Crosby Hall, showed a lively sense of gratitude by allowing the old servant to retire in comfort and ease to the restful shelter of Lady’s Bower.

And not only this, but Lady Crosby took from the very first a special interest in Mrs. Lubbock’s youngest daughter, Lucy. Her quick, sympathetic eye had seen Lucy’s unusual possibilities when the girl was still a small child, and she insisted upon giving her the best of educations, and finally equipping her for the profession of nursing, her chosen field. To the rest of the village, however, these attentions smacked of favoritism, and there was much tossing of heads, and self-righteous comment on how “some people do give themselves airs.” The result was that, though Mrs. Lubbock was happy in Lucy’s success and devotion to herself, she was often lonely and sadly in need of a neighbor to pass the time of day or drop in for a cup of tea.

Sir Howard Crosby, too, while allowing Mrs. Lubbock’s right to a generous pension, could not quite reconcile himself to the idea of squandering such perfection as Lady’s Bower on a “mere servant.” In times gone by, when blood ran hot in the Crosby veins, Lady’s Bower had been all that its name implied—an amorous trysting place where the Lord of the Manor could forget his cares and domestic worries in the arms of some fond lady, or a cheerful asylum where he could fight his battles over again among a convivial gathering of his friends. Not that the present Sir Howard had any desire to re-establish Lady’s Bower in its old capacity. For all his cavalier tradition, Sir Howard might have been the last of the Roundheads. No, it was another and less romantic consideration that moved him. He could have rented it many times

over on enormously profitable terms, and even now was negotiating with a rich American artist who had an expensive taste in rural seclusion. Thus, though Mrs. Lubbock had a strong ally in Lady Crosby, she nevertheless was always aware of the spectre of dispossession hanging over her head like another sword of Damocles.

On this particular afternoon in June, as the minutes passed and Lucy did not come in, Mrs. Lubbock pulled up her chair to the table again, and took up the tea-pot.

“I think I’ll pour the tea now and not wait for our Lucy,” she said. “She’s very late. I’ll keep the kettle on the boil and make some fresh for her when she comes.” An eternally boiling kettle against an emergency cup of tea was Mrs. Lubbock’s Eleventh Commandment.

“Not much good waiting for her,” sniffed Isabel, “she’s probably out a-gallivanting with young Crosby, if what I hear in the village is true.”

“Yes, ma,” interrupted Amy, who had once been the village belle and still fostered romantic ideas, “we met Cockett as we came up from the station, and he told us that young Dr. Crosby is fair took up with our Lucy. What with her being a nurse at the Cottage Hospital, and his being an internal—or whatever it is they call someone who is nearly a doctor—they must be seeing quite a deal of each other!”

“You would be pleased, Amy. You’re that shortsighted!” snapped Isabel, whose own romantic leanings had had less scope than Amy’s. She was not so attractive as her two younger sisters, and it made her impatient to hear of their amorous conquests. “I’d like to know what Lady Crosby thinks of it,” she went on. “For all she’s so sweet to us I’ll warrant she wouldn’t stand for no sweethearting in that quarter, and it’s out of Lady’s Bower you’d go, ma, yes, and Lucy too.”

“Hush, dear,” said her mother, who still cherished a happy faith in the infallibility of the aristocracy, “you shouldn’t even think of such things, and I don’t take it at all kindly in you that you speak like that about Lady Crosby after all she’s done for you girls—getting you your posts up in London, and educating Lucy to be a nurse and all! Such a generous creature as she is too! Why, just before she went away she sent over her usual half yearly gift—a whole ham, some eggs and tea and sugar and even something extra this time—two big bottles of her own special sloe gin.” Isabel snorted and buried her sharp nose in a teacup.

“And as for turning us out,” continued Mrs. Lubbock calmly, as she dropped a lump of sugar in Amy’s second cup of tea, “who do you think dropped in to-day? Why, Sir Howard himself, and that handsome Miss Darcy—her as they say the young squire be goin’ to marry. He was most civil-like—had a nip of his wife’s sloe gin he did—and Miss Darcy too! ‘Mrs. Lubbock,’ he says, ‘my lady has interceded for you, and I’m going to let you stay on here—for the time being, at least—though if you knew how much money I’m losing by it you’d say I was crazy!’”

“That would make two crazy people that have lived at the Hall,” retorted Isabel sharply; “what with that old looney mother of Lady Crosby’s with her rantings and ragings—”

“Bella, dear,” said Mrs. Lubbock, whose professional feelings were now seriously shocked, “you mustn’t speak ill of the dead that way—not even of poor old Mrs. Burwell, God rest her soul. She may have been a thorn in the flesh to me, but the Lord has given us our stations in life to do our duty in them as best we may.”

Before Isabel had time to criticize her mother’s simple philosophy, the door of the cottage opened, and Lucy—Mrs. Lubbock’s youngest daughter—came in. There was a noticeable change in atmosphere as the two older girls took stock of their sister’s loveliness, for Lucy’s beauty was rather breathtaking to those who were not accustomed to seeing it daily. The nurse’s simple costume set off to perfection the straight, classic lines of her figure, while the starched linen cap made an exquisite frame for her dark, lustrous hair. Her complexion was of the strawberries and cream variety—a perfect blend of pink and white which “Nature’s own skilled and cunning hand laid on.” Her eyes were grey and candid, yet with enough hidden sparks lurking in their depths to denote character, ambition and firmness of purpose. Lucy seemed to combine the gentleness of her mother and Amy with the courage and outspokenness of Isabel.

Removing her cloak, she kissed her sisters, welcoming them affectionately, and then insisted that they all join her in a cup of fresh tea that Mrs. Lubbock had prepared. For a while the three sisters looked at each other a little awkwardly, each awaiting the cue to speak. The two older girls found themselves in some awe of this younger sister who had been, when they last saw her, still a growing girl, and since that time had come into such a heritage of poise and beauty.

“My, Lucy!” said Amy admiringly, “you are looking well. And quite the nurse!”

“H’m, yes,” added Isabel with a touch of acidity, “and I can actually smell the hospital on your clothes.”

“There was rather an important operation this afternoon, Isabel, and I was on duty. That’s why I am so late. I’ve got to go back again in a very few minutes, but I wanted to come over and welcome you home. Dr. Crosby is coming to fetch me in his car quite soon—it’s an urgent case and I shall probably be at the Cottage Hospital until quite late.”

Dr. Crosby is coming to fetch you, Lucy,” said Amy, who already visualized herself as the sister of the beautiful Lady Crosby, “since when did the young squire act so attentive?”

“Since poor old Joe Birch’s life depended on his having someone to nurse him properly,” said Lucy coolly, as she helped herself to a slice of generously buttered toast and passed the milk jug to Amy. “It’s almost six now and he will be here at any minute. But there’s nothing to get excited about, Amy. Dr. Crosby is studying medicine up at Guy’s hospital in London, and being home for a few weeks he has naturally dropped in to the Cottage Hospital quite often to help Dr. Hoskins, who thinks the world of him.”

“Well, don’t say as we didn’t warn you, Lucy,” said Isabel, “I’ve been in service with the gentry long enough to know that no good ever came of that sort of thing.” Isabel liked to drop occasional dark hints which might lead the hearer to suppose that she had ample opportunity to become the plaything of some rich nobleman! “And my advice is that you don’t let them know up at the Hall or—”

But the sentence was never finished, for at that moment there was a knock at the cottage door, and a tall, redheaded young man with merry eyes stood on the threshold, smiling apologetically.

“How do you do, Mrs. Lubbock,” he said, holding out his hand, “I’m sorry to break up a family gathering like this, but, before I carry Lucy away perhaps you will be kind enough to let me join you in a cup of that tea I see brewing. No milk or sugar thanks—I take my drinks neat.”

Mrs. Lubbock could hardly restrain herself from dropping a curtsy, as she said, “Why, yes, indeed, Mr. Christopher—er—Dr. Crosby, I mean—make yourself at home.”

“You know my two sisters, I believe, Dr. Crosby,” said Lucy calmly, as she poured out a cup of tea for the visitor.

Christopher Crosby shook hands with the two older women and welcomed them home. Then he started to chat with them all in the most natural manner about the doings of the village, Joe Birch’s chance of recovery and other local matters. By the time he and Lucy left in the Morris Cowley even Isabel felt obliged to remark that “at least he wasn’t as stuck up as some of the nobs, though there was no reason why he should be seeing as how the Lubbocks were probably living on their own lands when the Burwells were just tinkering around the country.”

After a while a few of the villagers dropped in to greet the two older Lubbock girls—Mrs. Greene from the Post Office, Miss Sophy Coke, who kept the tiny village store, and finally William Cockett, Amy’s oldest and most ardent admirer. It was many months since a casual visitor had crossed Mrs. Lubbock’s threshold, and she beamed expansively in a genial atmosphere of tea and gossip.

The sloe gin and the tea-pot circulated freely as they talked of the local doings—Lady Crosby’s absence, the illness of

old Joe Birch who had been gardener at the Hall for many years, and the thrill of having “the young squire” at home again. There was a word of guarded praise for Dr. Hoskins who had recently taken over old Dr. Crampton’s practice (“he do seem quite reasonable in spite of his newness and withal a quiet sort of man in need of a wife”), and a detailed account of the probable rashness and unsuitability of all the recent marriages and betrothals in the village. The two girls sat back and listened, or put questions—Amy with obvious interest and good humor, Isabel with just that touch of condescension which implied habitual intercourse with the great.

Finally Cockett manoeuvred Amy into a corner and suggested a twilight stroll.

“No, Will,” she answered firmly, trying to smother an all-too-obvious yawn, “I’m pretty tired after my journey, and bed is the place for me. Mother, can I have a candle, please?”

Amy followed her mother into the back kitchen where she lighted a candle.

“Mother, dear,” she said suddenly, “I followed you out here because I wanted to get away from Will, and also because I wanted to speak to you alone for a minute. I’m worried—it’s about Isabel—she’s been acting strange lately, and I think she’s got something on her mind. Have you noticed it? I’ve seen her several times in town, on her afternoon’s off, and she’s seemed kind of queer, and whenever I’ve spoken of doings at home, and you and Lucy and the Hall she’s laughed that queer laugh that she didn’t used to have—as if she thought we were all fools—kind of harsh and frightening.”

Mrs. Lubbock looked intently at her daughter, but was silent. “She doesn’t love me like she used to,” Amy went on, “or I’d speak to her about it, but I thought that you—”

“Let’s talk about it to-morrow, dearie,” said Mrs. Lubbock with a sigh, “it’s no good worrying about things we don’t rightly understand, and you are tired now and need sleep.” They kissed each other affectionately.

Death Goes to School

Death Goes to School Hunt in the Dark

Hunt in the Dark The Cases of Lieutenant Timothy Trant (Lost Classics)

The Cases of Lieutenant Timothy Trant (Lost Classics) Death for Dear Clara

Death for Dear Clara S.S. Murder

S.S. Murder Death and the Maiden

Death and the Maiden The Grindle Nightmare

The Grindle Nightmare Cottage Sinister

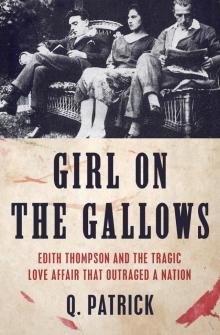

Cottage Sinister The Girl on the Gallows

The Girl on the Gallows