- Home

- Q. Patrick

Cottage Sinister Page 3

Cottage Sinister Read online

Page 3

Dr. Hoskins nodded in agreement. As his recent predecessor, Dr. Crampton, had been one of the most popular men in the village, he was very anxious to do the right thing by the natives of Crosby-Stourton. Suddenly an idea struck him.

“Yes, and at the same time we could have him examine her to see if—well, you know, Crosby, she’s not at all bad looking and perhaps some fellow got her into trouble. If so, it’s quite within the range of possibility that she committed suicide.”

“Nonsense,” said Christopher with some warmth, “I’ve known Amy Lubbock in the village for years. Her head was screwed on as right as a trivet, Hoskins—you know, calm, cow-like and rather slow witted. None of the appasionata stuff about her. Besides, when poor servant girls want to do away with themselves they swallow lysol, iodine, ammonia—anything that’s handy on the spur of the moment, and it’s one of our jobs in hospitals to get it out with a stomach pump. If Amy Lubbock died from poison—which I doubt—it was a poison she couldn’t possibly have procured for herself, unless—” he did not finish his sentence. Instead he walked to the window and stood looking out past the sprays of jasmine to the lilies below.

“Then you think,” said Dr. Hoskins slowly and with emphasis, “you think it’s probably—murder!” Christopher started perceptibly. Then he turned and faced his companion with a troubled expression which belied his air of nonchalance.

“I think nothing of the sort, Hoskins. There is only one person in Crosby-Stourton who is capable of doing a thing like that, and she—heaven be praised—has been dead for over two years.”

“And who is that, may I ask?” Dr. Hoskins’ eyes were looking serious through his thick spectacles.

“Well, the joke is wasted on you, Hoskins, because you didn’t even know her, but I am referring to my maternal grandmother—the late lamented Mrs. Burwell!”

Mrs. Greene, who presided over the village Post Office, never let you forget that she was one of His Majesty’s Servants. If King George had come to Crosby-Stourton in person with the express purpose of placing plenipotentiary powers in her capable hands, she could not have carried off her position with greater dignity and magnificence. She breathed a divine afflatus on the sale of a half-penny stamp and imbued even a shilling postal order with weighty importance and officialdom. When it came to telegrams—and it didn’t very often in Crosby-Stourton—she surrounded their dispatch with a positive halo of mystery and romance, always managing to give the sender the impression that his awful secret was safe in her royally-consecrated hands. As for broadcasting to her neighbors any information obtained from one of these important missives—perish the miserable thought! The village arcana were as safe, when locked in her capacious bosom, as if they had been confided in His Majesty’s own personal ear!

And so, when Doctor Hoskins left Lady’s Bower and entered the picturesque thatched cottage which served as the village Post Office, he was greeted by Mrs. Greene in her most official manner. The news of Amy’s death had already got abroad, and it is greatly to the credit of the postmistress that she did not betray, even by the flicker of an eyelid, the curiosity with which she was consumed. With care that amounted almost to cunning she concealed her inquisitive-ness and merely passed a few vague remarks about the weather or asked after Dr. Hoskins’ roses. From the magnificent nonchalance with which she took the two telegrams, counted the words and made change, any casual observer would have sworn that they contained nothing more significant than a bon voyage message to a maiden aunt!

After the doctor had left, she read them over carefully—just to be sure that she had made no errors in her computations! Then she skipped (with remarkable agility) into her back parlor and produced a well-thumbed dictionary—just to make certain that she had spelt all the difficult words correctly!

The first ran:

County Pathologist, Taunton, Somerset, Kindly arrange for an immediate autopsy on a case of inexplicable death in Crosby-Stourton stop symptoms point to possible poisoning and may need official investigation.

Joseph Hoskins.

The other read:

The Dormital Company, 12 Bay Street, Manchester. Wire immediately formula of Dormital Tablets and any information that might account for sudden and inexplicable death following their use.

Doctor Joseph Hoskins,

Crosby-Stourton, Somersetshire.

Now there were several places in the two telegrams where even the dictionary did not help Mrs. Greene very much, but the general significance was extremely gratifying. For had she not with her own eyes seen Amy alive and blooming the previous evening, drinking sloe gin with the best of them and flirtatiously warding off the advances of William Cockett? And did it stand to reason that the same girl should be found cold and dead in her bed, the very next morning, from natural causes? Mrs. Greene prided herself on a certain astuteness of mind, especially where the misfortunes of her neighbors were concerned, and it was a relief to know that even a clever young man like Dr. Hoskins found something to puzzle him in this case, something that might even call for official investigation, whatever that meant! Mrs. Greene drew a deep breath which implied a Cassandra justified, and called to her daughter Nora.

Thinking that, under the circumstances, His Majesty’s Service might well spare her for a while, she gave Nora minute instructions as to her probable whereabouts in case of emergency, turned her back on the stock of lollypops and ginger bread which constituted a profitable sideline to more official business, and proceeded to go out. With mouth tightly pursed and an inward vow that no inside information should pass the portal of her lips, she went calling on her neighbors to “see how much they knew.”

She found the village agog with excitement. Poor old Mrs. Birch whose recent bereavement would normally have made her the most talked-of woman in Crosby-Stourton, was complaining bitterly that “from all the attention she’d a been getting anyone might think that a body lost her old man every day!” Miss Sophy Coke, like the respectable spinster that she was, inveighed darkly and bitterly against the dangers of town life and dropped sinister hints about the awful possibilities contingent upon a too close association with the aristocracy. P. C. Buss, the village strong arm of the law, twirled his enormous black mustache and whispered to a few intimates that he “couldn’t interpolate until importunited by the parties concerned, but that presumptuously it was only a matter of moments before he was authenticated by some one.”

Poor William Cockett, whose very obvious grief made him temporarily immune from approach, had not yet been drawn into the maelstrom of gossip, but it was supposed that he knew a thing or two if only he could be prevailed upon to speak. As for Lady’s Bower—even the hardiest had not yet dared to brave the wrath of Isabel, who, throughout the morning, had stood at the door of the cottage like an Angel with a Flaming Sword to guard her poor prostrate mother against unwarranted intrusions.

Let it never for a moment be supposed that Mrs. Greene so much as breathed a word of what she had read in the telegrams. She listened very carefully to all that was told her and then went on her mute and mysterious way. And yet—somehow or other—her very silence, coupled with various noddings and shakings of the head and an attitude of “I could a tale unfold” was more pregnant of wild rumors than if she had disclosed the whole contents of Dr. Hoskins’ dispatches. At any rate, by noon time, the village was convinced that something was “rotten in the state of Denmark,” and one heard such terrible assertions and forebodings as “It’s my belief as how a fiend is at work,” or “The Lord alone knows who will be the next,” and the number of people who had seen a dark stranger hanging around the cottage on the previous evening grew to quite alarming proportions!

After lunch Mrs. Lubbock had recovered sufficiently from the first shock of her grief to receive sympathetic solicitations from Sir Howard Crosby and Miss Vivien Darcy. Their visit touched the old lady and comforted her strangely. By tea-time she was ready to see a carefully picked group of friends and was quite prepared to talk freely of her sorrow. The majesty of grief bec

ame her well. Though her neighbors were far too delicate to mention the fact that they would like to see the body (a normal request under normal circumstances), there was, none the less, a noticeable current of excitement running through the assembly when Mrs. Lubbock sadly suggested that “they might like to see the last of our poor dear Amy.” Isabel conducted them upstairs, grudgingly enough, one by one, and they all shook their heads and made appropriately pious comments in an attempt to hide a thoroughly secular curiosity.

It was Mrs. Greene who had acted as spokesman for the little party during this visit. Her official title of Postmistress naturally gave her precedence. It is to be supposed, therefore, that she voiced the general opinion when she refused Lucy’s offer of tea. Her actual words were perfectly polite, “Oh, we couldn’t think o’ troubling you in such sad circumstances,” but, with her gift of conveying impressions without giving them tongue, she managed to suggest that she at least would prefer to find an asp—a viper—a poisonous toad in her cup than any tea of Lucy’s brewing. Immediately afterwards, when Cockett entered the cottage, she shepherded her little flock outside, and as they passed down the road in the summer twilight, she shook her head darkly and murmured to Miss Coke, “there’s more to come, Sophy. Mark my words, there’s more to come, and the Lord alone knows who’ll be took next.”

William Cockett, at best a rather sombre individual, looked haggard and wretched as he came in and took Mrs. Lubbock’s hand. Although Amy had never responded to his wooing, her sudden death had been a profound shock to him and he gave the impression of being a broken man. Without even a pretence at making conversation with the three women he insisted on going upstairs and staying alone with the body, and when he finally was persuaded to come down and take a cup of tea with the family, he could not be prevailed upon to say a word.

The situation had reached an impasse when Christopher dropped in—this time as a friend of Lucy’s and not in his role of physician. He did his best to be cheerful, but the tea-party was a sad enough affair which served only as a poignant reminder of the previous day and of how happy they had all been before death had claimed one of their number.

Just as evening shadows were beginning to fall there was a low rumble of heavy wheels outside the door. It was the ambulance from Taunton.

“Oh God! they’ve come for our Amy,” cried poor Mrs. Lubbock with a low moan, as Dr. Hoskins, followed by two white-clad stretcher bearers entered the cottage. Lucy went to her mother’s side and tried to comfort her.

While the bearers followed Isabel upstairs, Dr. Hoskins called Christopher aside, and, pulling a telegram from his pocket, said, “Guess we must give the Dormital Company a clean bill, Crosby. The stuff’s nothing but a triple bromide and as harmless as possible. The whole bottle of tablets couldn’t have killed her unless it had been doctored in some way.”

Christopher read:—

Dr. Joseph Hoskins, Crosby-Stourton, Somersetshire, Dormital contains two grains sodium bromide, two grains potassium bromide, two grains ammonium bromide with starch as excipient stop slight rash might follow extensive use but death or serious results impossible stop management desirous to clear itself so kindly send further particulars.

E. J. Aiken,

President, Dormital Company.

“I never did think they were responsible, Hoskins,” said Christopher, as he returned the telegram. “Proprietary remedies are pretty careful these days, but we might as well have the public analyst check up on the remaining four tablets just to see if they really are true to formula.”

At this juncture they were interrupted by the stretcher-bearers, who came downstairs carrying all that was mortal of Amy Lubbock. To Dr. Hoskins was left the unpleasant duty of asking Mrs. Lubbock to sign the paper authorizing an autopsy—one of the most disagreeable tasks a physician has to perform, but necessary in this instance since the regular coroner for the district was away. After some demur, all the final arrangements were made, and Dr. Hoskins turned to his colleague, saying quietly,

“I’m going to Taunton on the ambulance, Crosby. It would be a great help if you could come along in your car and bring me back. Incidentally, I’d like you to corroborate my medical findings—we could both get home by eleven o’clock.”

Christopher consented willingly, and the party moved on to Taunton, leaving the Lubbocks and Cockett alone with their grief. For some time the four of them sat silent in the fast-gathering darkness of the evening. The carpenter was at the window staring unseeingly out into the fragrant garden. Isabel sat at the tea-table where the cups and saucers were still waiting to be cleared away. Occasionally she would take a sip of cold tea in a listless manner. Mrs. Lubbock was crying softly to herself in her large arm-chair. Finally Lucy rose and started to light the lamps. The atmosphere of the cottage was beginning to tell upon her nerves. There was no sound from outside except when the evening breezes blew a rambler rose or a spray of creeper against the window panes.

Suddenly Isabel’s voice—hoarser than usual—broke the silence.

“Oh, my God, Mother!—what’s he doing there—the other man?” She pointed at Cockett with trembling fingers.

Lucy put down the lamp and ran to her sister’s side. ’’What is it, Bella?” She asked nervously, “what do you mean-there’s only Will Cockett there.”

“There are two men there,” muttered Isabel, “and—Oh, God! now there’s two of you, Lucy.” She coughed slightly. “I don’t know what is the matter with me, but my throat is on fire. Water, water!” Her eyes were staring terribly, and she lay back, slumped in her chair.

Lucy ran to fetch water and Isabel drank greedily. “Hark! it’s the van coming back,” she said at last in a strangled voice, “the van and a policeman coming with it—for me—he’s over there now,” again she pointed towards Cockett, “the policeman that murdered Amy! Don’t you hear the van, Mother,—Mother, I can’t see anything,” her voice was getting fainter and fainter, “she’s dead—our Amy—poisoned, just as I am and it’s my fault. It’s my fault, or Myra Brown’s—curse Myra Brown—Myra Brown—” her voice rose to a weird screech and she fell unconscious on the floor.

For a moment the three onlookers did nothing but stare at Isabel in horror—they seemed almost paralyzed at the awfulness of the spectacle. Lucy, the first to recover her wits, turned towards her sister, and with Cockett’s help, lifted her on the horse-hair sofa.

“Quick, Will,” she said breathlessly, “run for Dr. Hoskins or Dr. Crosby.”

“Reckon the two doctors be halfway to Taunton by now with poor Amy,” said the man morosely.

“What shall we do—what shall we do?” moaned Mrs. Lubbock, when she saw that Isabel failed utterly to respond to Lucy’s attempts at reviving her.

Cold compresses, simple emetics, brandy—all were tried, but to no purpose. Isabel lay on the sofa lifeless, the thin pulse at her wrist growing weaker and weaker beneath Lucy’s experienced fingers. Without any sense of time or place the young nurse worked like a slave, but it was to no avail. Towards midnight, the two doctors, who had been summoned by Cockett after their return from Taunton, found Lucy lying in a state of complete exhaustion by the dead body of her sister Isabel.

Christopher’s face was as white as death as he helped Dr. Hoskins to carry the girl upstairs and administer a hypodermic injection to her and Mrs. Lubbock. When they finally came downstairs again they found Cockett still waiting by Isabel’s dead body. He gave them a simple version of the tragedy.

“Well, there’s no doubt in my mind now that both girls were poisoned,” said Dr. Hoskins, when the two physicians, were left alone to make a more detailed examination of the body.

“And now that I’ve heard Cockett’s story,” said Christopher, “I don’t believe I need to dip into a handbook of Toxicology or Pharmacology to say what drug was probably used—though how anyone here could have got hold of it—” he broke off suddenly.

Dr. Hoskins looked up quickly at the pale face of his colleague. The light of scientific adm

iration shone in his eyes. “Well, you are one jump ahead of me, Crosby—”

“Why, man, it’s as plain as the nose on your face,” continued Christopher wearily, “here’s a drug which induces a state of sleep or stupor after a period of agitation and apparent mental derangement—more or less marked according to the temperament of the victim, the size of the dose, etc., etc. In Isabel’s case the agitation was pronounced—in Amy’s, less so. The first symptom is a burning or dryness of the throat—you remember Amy complained of that to Isabel—” Dr. Hoskins nodded. “Then restlessness—dual vision—Cockett said that Isabel looked at him and spoke of the other man—followed by almost unintelligible murmurings (which may have been pretty important, by the way), and finally stupor and death from respiratory failure.”

A look of horror passed over Dr. Hoskins’ stern young face, “You don’t, you can’t mean hyoscine or any of that atropine group, Crosby! Why, you know as well as I do that it’s altogether impossible for the layman to get hold of it except on prescription and then the maximum dose is about one-sixtieth of a grain! Damnable stuff, anyhow, in my humble opinion. I always use luminal at the hospital and in my practice—”

“Yes, Hoskins, I do mean hyoscine, or scopolamine if you want to give it its proper name. The stuff they used to mix with morphine to produce the so-called ‘Twilight Sleep’ in obstetrical cases some years ago. It’s still used pretty widely by itself, even now—Thornton of Guy’s uses it in the neuroses, epilepsy, manic frenzies, delirium tremens, etc. It’s safe enough if a doctor is handy to take the right measures in case of overdosing. If you ask my opinion, the pathologist will find that hyoscine is responsible.”

“But the fatal dose is so tiny, Crosby, that I doubt if it would be recoverable in the stomach. Two or three grains at most—God, what a mess!”

Christopher shrugged his shoulders helplessly, “Well, whatever it was, it looks like murder all right, all right. And I suppose you’d better telephone the authorities straight away; in the meantime we’ll see if there is anything we can do here to help them when they come. Look, the tea things are still on the table; we might as well lock everything up for examination.” He called to Cockett who was waiting dejectedly on the porch.

Death Goes to School

Death Goes to School Hunt in the Dark

Hunt in the Dark The Cases of Lieutenant Timothy Trant (Lost Classics)

The Cases of Lieutenant Timothy Trant (Lost Classics) Death for Dear Clara

Death for Dear Clara S.S. Murder

S.S. Murder Death and the Maiden

Death and the Maiden The Grindle Nightmare

The Grindle Nightmare Cottage Sinister

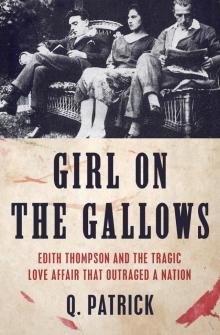

Cottage Sinister The Girl on the Gallows

The Girl on the Gallows