- Home

- Q. Patrick

Hunt in the Dark Page 10

Hunt in the Dark Read online

Page 10

“The autopsy’s completed,” he heard. “No news except that the weapon was possibly poisoned or dipped in some dope. The glass was no help—only a reasonably strong sleeping draft.”

“Thanks, doctor!” There was excitement in the inspector’s voice. “And, listen, I want you to come over here this evening, just before seven. I’m going to throw a party. Yes, the old gag. Maybe we’ll get a breakdown.”

Night had settled round the house. Inside, the curtains were drawn. A grim-faced policeman conducted the two doctors and Miss Hazeldean into the patients’ waiting room. Myra van Holdt was absent, Doctor Barry having insisted that she was too ill to leave her room. Groves and the medical examiner were waiting by the door of the office.

“Please follow me,” said the inspector.

Silently, they all trooped into the darkened room.

All the lights had been extinguished except one tiny, shaded bulb beneath the clock. Here and there one could make out the nebulous forms of chairs, bookshelves, and lamp stands. On the couch lay what looked like a sleeping figure.

Someone gave a little gasp, and then silence—utter and motionless—reigned. Every eye stared at what, for an instant, seemed to be the body of Julius van Holdt. Only gradually did the truth break through to them. It was a dummy. The bulk of it was made from cushions, the head a toy balloon, crudely painted with the markings of a human face!

The house was as still as a tomb. Crashing through the stillness came the ticking of the clock. In contrast, the inspector’s voice sounded low and hollow.

“Throw your minds back twelve hours,” he said. “Imagine it is this morning, just before Julius van Holdt met his death. Everything in this room is exactly as it was then. I have even put the weights of the clock in the same position. In a few moments, you will find out exactly how the murder was committed.”

The clock ticked on. It was barely possible to pick out the lines of its black metal frame; but just above the dummy—seeming almost to touch it—hung two indistinct shadows, looking darker against the blackness of the wall. They were the lead weights.

Louder and louder, the seconds shouted themselves by. Nerves grew more tense. Every one breathed quickly, keeping time unconsciously with the rhythm of the clock.

Suddenly there was a little scraping sound as though a mouse were nibbling at the wainscoting.

Everyone strained forward, trying to pierce the gloom. Then, without warning, the silence was split by a sharp noise from the couch—an explosion which cut through the air like a pistol shot. Barry started violently and overturned a chair.

“What was that?” someone shouted, and there was a general cry for lights.

Groves’s voice rose calm and clear above the confusion. “Don’t worry. It was only the balloon bursting,” he called out, and then, putting a hand on the switch, he flooded the whole room with a blinding glare.

The dummy lay straggled on the couch, but now it was only a bundle of cushions and, where the head had been, a few limp strands of India rubber. Just above them, like a great, gray toad, squatted one of the heavy lead weights.

The inspector crossed the room briskly, fumbled under the weight for a moment, and then held up something that glinted coldly. It was a long needlelike instrument—a surgical probe.

“You see now,”—his voice was quiet and efficient—“how the crime was committed. Last night a needle like this one was wedged into a hole in one of the weights.”

As they pressed eagerly forward, Groves pointed out the silver edges of a recent hole in the scarred lead.

“The weights drove the needle downward until it pierced the victim’s brain,” he continued. “You yourselves didn’t notice the weapon, even when I switched on the light. And van Holdt, intoxicated as he was last night, would not have noticed it either.”

“But how on earth—“ the medical examiner began.

“We may be fairly certain,” Groves explained, “that the job was done by someone who knew van Holdt’s habits. Even if the needle had not been dipped in some anesthetic, his heavy drinking and the strong dose of bromide would have been enough to prevent the pain from waking him. Of course, there was no way of making certain that the needle would strike exactly on the eye, but there was quite a chance of it piercing some vital spot.”

He looked searchingly round at the pale faces in front of him. “Someone in this room did it,” he said, and swung back toward the couch. “Do you see this couch? It is back against the wall. I pushed it there myself. Normally, Doctor Cobden tells me, it is kept at least a foot away so that he can get to both sides of the patient he’s examining. The murderer pushed it in last night so as to make it possible for the weight to come down over the face—and then pulled it out this morning. I learned that when I discovered a stubbed cigarette under the couch. Van Holdt couldn’t have reached under that far if his bed had been in its normal position. He would have stubbed it on the floor by his side.”

Groves paused dramatically.

The first sound that broke the silence came from outside the room. There was a faint tap, and a policeman pushed back the heavy folding doors. A woman stood on the threshold—a small, tragic figure. It was Myra van Holdt.

Doctor Cobden led his daughter to a chair.

“Mrs. van Holdt,” Groves resumed, “we know how your husband was killed. We know also that his murderer wound up the clock and removed the needle before nine-twenty when I came in. Any member of the household could have done it. You all had the means, the medical knowledge, and motives.” Groves’s voice rose.

“You”—the inspector swung toward Doctor Cobden—“you admit you strongly resented van Holdt’s treatment of your only daughter.”

The old man’s face clouded.

“You, Miss Hazeldean,” Groves said, “were more than friendly with van Holdt up till the time he heard about his wife’s inheritance—and then he dropped you. You had every reason to hate him.”

“I wasn’t the only one,” said the girl bitterly. But Groves was now looking at Doctor Barry.

“And you,” he cried, pointing a finger toward the young doctor, “you cannot deny that you felt strongly about van Holdt’s abuse of the woman you—“

“Will you please mind your own damned—“

“This is my business,” snapped Groves. “There’s Mrs. van Holdt, too.”

“I didn’t do it. I didn’t!” Myra van Holdt had risen to her feet and stared wildly around her.

Barry turned toward the inspector.

“Good heavens, man, can’t you leave her out of this? She’s sick!”

“I make no accusations—as yet,” said Groves quickly, and there was a curious gleam in his eyes. “Now, let’s get back to the subject of this clock. The person who was calmly able to wind it up when the dead body of Julius van Holdt lay there on the couch is obviously the murderer. Doctor Cobden, please step here.”

The doctor came forward.

“Now will you please wind up the clock?” Groves requested.

The old man reached up one of his long, thin arms and, taking the key from a hook, started to wind.

“That’s enough,” snapped Groves. “Now, you, please, Doctor Barry.”

With an impatient shrug, the tall young doctor crossed the room and went through the same movements.

“Thank you.” Groves took the key and gave it to the medical examiner.

The little man accepted it.

“Do you mind winding it up, doctor?” Groves asked.

The medical examiner walked over toward the clock and reached upward. He was too short by about four inches. Placing one foot on the part of the couch where the head of the body had lain, he connected the key with the dial.

“Hold it, doctor!” cried Groves.

As the little man stood there, perched in mid-air, the inspector continued.

“This morning I found a muddy patch on the couch in almost exactly the place where the medical examiner i

s now standing. It was a footprint—the footprint of someone who had been in a hurry—of someone who, like the doctor there, was not tall enough to wind up the clock without stepping on the couch.”

“Can I get down now?” interrupted the medical examiner. “O.K., doctor, and thanks.” Groves could scarcely conceal the

ring of triumph in his voice. “It was the footprint of a person who was ready to take an enormous chance—of someone motivated by a violent and uncontrolled passion—someone whose feeling for van Holdt had been changed to hate. And—most important of all—it was the damp footprint of someone who had recently come in from the wet streets—of a person clever enough to have an alibi, but not clever enough to remove two pieces of damning evidence.”

His voice seemed to smash through the room as he pointed toward the farthest corner. “Would you please show us how you would wind up the clock? You, I believe, were the only person who had damp feet this morning!”

There was no answer. All eyes were turned toward the secretary.

“Miss Hazeldean!”

But again there was no answer, and this time all eyes were fixed on a crumpled mass where a woman lay on the floor in a dead faint.

The Hated Woman

I

A SELFISH WOMAN

Life was easy for Lila Trenton—too easy. And yet she was discontented. Even now, when she had just awakened safe and warm beneath her rose-colored quilt, there were little lines of discontent around her mouth. Her movements were petulant as she fingered the hairnet which preserved the stiffness of her hennaed waves. Restlessly, she stretched her silk-covered limbs, which, despite a slight thickening, were still well molded and voluptuous.

Through the wall she could hear her husband’s slow, indecisive footsteps as he moved about his separate bedroom. For the thousandth time she wondered why she had married Paul Trenton. She, the pretty Lila, deserved something so much better than this dried-up, useless stick of a man.

She looked back to the time when she had first met him. Then he had seemed so distinguished, and everybody had said he was going to become famous with those chemical experiments of his. Lila Trenton—wife of the celebrated Paul Trenton. That’s what she had hoped to be. Well, he had fooled her. Fifteen years had gone by, and he was still just an ordinary research worker down at the university—never made more than two thousand dollars a year.

Lila Trenton despised her husband because she had money and he had not; because he worshiped her slavishly despite her indifference to him; because she had perfect health, whereas he, who never complained, seemed to look older and frailer each day.

The careful footsteps had passed through the living room to the kitchen. Soon they returned, and there was a soft tap on the door.

“Are you awake, dear?”

A sallow, middle-aged man with graying hair slipped into her room, carrying a cup of tea in uncertain fingers. “I’ve brought the tea rather early, dear. I want to be at the laboratory by ten. There are some interesting developments.”

“There’ve been interesting development for fifteen years,” snapped Lila as her red-nailed hand reached for the cup. “Oh, Paul, you’ve slopped it all over the saucer!”

“I’m sorry.” Paul Trenton’s pale, sensitive face regarded her with anxious attention. “How do you feel this morning, dear?”

“Feel! It’s too early to feel anything.”

Paul Trenton drew back the curtains and the morning light fell full on his tired face.

“He does look old,” Lila was thinking not without a certain satisfaction. “Anyone seeing us together would take me for his daughter.”

She stirred the tea, crushing three lumps of sugar with her spoon. “You look simply terrible, Paul. I suppose you’ve been working all hours of the night with those crazy experiments of yours. You never think how dull it is for me sitting all day alone with nothing to do but read magazines and listen to the radio.”

“I had no idea you were lonely.” Her husband’s lips curved in a slight smile. “But you won’t be alone tonight, dear. I’ve asked Professor Comroy for dinner. I hope—“

“Oh, Paul,” —the cold cream on Lila’s face puckered into lines of irritation—“you know how I hate fixing dinner for those stuffy university friends of yours.”

“We can have dinner sent up, dear.” Paul Trenton took the empty cup patiently and laid it on a table. “And Comroy is the head of my department. I owe him a great deal.”

“Well, it’s quite out of the question tonight,” snapped Lila. “I don’t feel up to it. And I think I’ve got a cold coming on. Yes, I’m sure I have. I just couldn’t cope with that—that old windbag.”

She sniffed with what conviction she could and produced a lace handkerchief from under the pillow.

“Very well, dear. I can put him off. And I’m sorry about the cold. Why don’t you spend the day in bed and take plenty of fruit juices?”

Lila had been staring meditatively at her expensively manicured finger nails. Suddenly she looked up, a crafty expression in her eyes. “There’s no reason for you to give up your date with Professor Comroy, Paul,” she said as though making a generous gesture. “Why don’t you take him out somewhere to dinner? I don’t mind an evening alone.”

“Why, that would be nice, Lila. If you’re sure you don’t mind.”

He bent to kiss her, but she pushed him away with bored distaste.

“Oh, Paul, not now! I can’t bear you to come near me in your working suit. It always smells of chemicals.”

She watched him move into the hall and heard the front door shut behind him. Then, with a curious, inward smile, she slipped her feet into feathery pink mules and hurried to the hall telephone.

“Hello, Larry… Yes, this is Lila. I’ve got a lovely surprise for you. I’m going to ask you round to dinner tonight… Yes, just us two. It hasn’t been that way for weeks, has it?”

There was a short pause at the other end of the wire. Then a man’s voice replied hurriedly, awkwardly.

“Well, Lila, I don’t know whether I can make it. Business is picking up, and there’s a lot to be done around the garage. But …”

“Oh, of course you’ll come.” Lila’s face had hardened, but her voice was silky smooth. “I know you’ll come if your own Lila asks you.”

“O.K. But listen, I’ve got to see you sooner than that.” The voice was curt now and determined. “Is your husband there? … Then will it be all right if I come straight away?”

“Oh, not now, Larry!” Lila gave a playful little scream. “Why, I’m hardly out of bed. I look a fright.”

“Never mind what you look like,” replied the man gruffly. “I’ll be there in half an hour.”

“Larry, Larry!” Lila jolted the hook, but the man had rung off. For a moment she stood by the table. Then she ran to the mirror in her bedroom and started to remove the cold cream from her face.

The image in the glass was entirely satisfactory to her. Although she was over forty, to herself she looked no more than twenty-eight. True, the gray was showing through at the roots of her hair. But she could have a touch-up before the evening. Her skin was still smooth and firm, and her eyes were as clear and lustrous as those of a young girl. There would be no time to heighten the interesting shadows beneath her long lashes. But Larry would be so pleased to see her, he would not notice little things like that.

While she worked at her toilet, Lila Trenton looked almost as young as she felt.

“Wanting to see me at ten o’clock in the morning!” she thought complacently. “These young men are so impetuous.”

II

CORNERED

Larry Graves slammed the receiver. As he gazed around the garage which he had bought and fixed up with Lila Trenton’s money, his young, almost too handsome face went grim. Swiftly he hurried into a small back room, slipped off his greasy overalls, and wiped the oil from his hands with a piece of cotton waste.

He felt utterly disgust

ed at the thought of the scene ahead of him. He could see Lila Trenton waiting for him, saccharine, seductive, and yet so predatory—so suffocating. Well, he’d gotten himself into this mess with his eyes open. He’d have to find some way out—anyway. Slicking down his thick blond hair, he took his coat from its hook and moved through the lines of parked cars toward an old roadster.

“Be gone about an hour, Jack,” he said as he swung open the door. “Finish fixing the brakes on that Dodd, will you?”

As he drove through the busy morning streets, the words Claire had spoken to him last night kept repeating themselves in his mind. “You’re nothing but a gigolo—a gigolo.” Well, she’d hit the nail pretty squarely on the head.

He drew up, outside the Vandolan apartment hotel, hurried into the opulent lounge, and, leaning over the desk, grunted a curt.

“Mrs. Trenton, please.”

Lila had left the apartment door ajar. She was carefully draped on a divan when Larry entered. The pink pajamas had been supplemented by a diaphanous pink wrap. It would have taken a more observant person than Larry to detect the hard work which had gone to create this tableau of seeming spontaneous charm. She held out both hands and crooned:

“Larry, how sweet!”

“I’ve got to talk to you,” said the young man shortly. He stood motionless by the door, clutching his hat in two bronzed fists. “It’s about the garage.”

“Come and sit here with Lila.”

Mrs. Trenton patted the edge of the divan invitingly and smiled. For an instant, the young man did not move. Then he walked slowly to her side and sat down within the range of her exotic perfume. His untidy, oil-stained suit was in striking contrast to the expensive elegance of her negligee.

“That’s better,” Lila was murmuring, taking one of his hands in hers. “Now tell Lila all the trouble and she’ll fix it.”

Death Goes to School

Death Goes to School Hunt in the Dark

Hunt in the Dark The Cases of Lieutenant Timothy Trant (Lost Classics)

The Cases of Lieutenant Timothy Trant (Lost Classics) Death for Dear Clara

Death for Dear Clara S.S. Murder

S.S. Murder Death and the Maiden

Death and the Maiden The Grindle Nightmare

The Grindle Nightmare Cottage Sinister

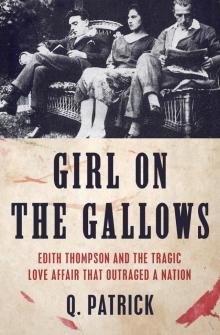

Cottage Sinister The Girl on the Gallows

The Girl on the Gallows