- Home

- Q. Patrick

S.S. Murder

S.S. Murder Read online

S.S. Murder

Q. Patrick

Foreword

I had this record from my friend, David Donnelly, of the New York Herald. He had it, so he claims, from the cellar furnace which, fortunately, was not burning when the manuscript was thrust there (more in sorrow than in anger) by his wife, Mary Llewellyn, the well-known columnist. I believe both Mrs. Lincoln and Mrs. Kipling made literary rescues of a somewhat similar sort—hence the Gettysburg Address and the “Recessional.” At any rate, the document was repudiated by its original owner for reasons clearly set forth on page 174. I have done little besides adding a few commas and the introductory letter, which I persuaded David to relinquish. I have also changed all names, and expurgated certain indiscretions not germane to the story. But above all I have tried not to destroy the quality of breathlessness which seems to make this record stand out from the synthetic mystery of fiction. Here, I thought, was a novelty—murder, written up, one might say, on the field of action. Here was emotion, not recollected in cold tranquillity, but poured on to paper while it was still molten, and before the final shape could even be guessed at. Here were living impressions of exciting incidents —informal without being formless and seen through the eyes of a trained writer who thinks with her fountain pen and knows how to manage her climaxes. For commas and footnotes I take credit. For the rest—my name is appended like a label on unclaimed baggage.

Q. PATRICK.

S. S. Moderna,

Friday, November 13th.

To David Hall Donnelly, Esq.,

56½ W. 12th Street,

New York City.

MY DARLING,

I must get a note off to you by the pilot, but it’s been such a little time, counted by minutes, since you kissed me goodbye, that I naturally haven’t much news for you. Did I remember to tell you, in the dust and heat of my departure, that I love you? Is that news, Davy? Well, it’ll be front page stuff in a little while—three months, three weeks and three days from today to be exact (see how I’ve reckoned it all out!) when you slip the ring on my finger and call me Mrs. David Donnelly for the first time. A real newspaper romance with torn up fragments of my Star and your Herald for confetti and yards of ticker tape for streamers.

We had so much better things to do than talk just before you left that I never told you, as I meant to, what I’ve resolved to do on this trip. Dr. Klein said I must sit quiet as much as possible, at least for the first week, so I’m going to keep a journal for you describing all the details of the voyage—all those intimate day-by-day happenings which may give you an idea of what really goes on in the head of the sweet young girl reporter whom you hope so soon to make your very own!

I know the doctor’s orders were NO WORK. But even the hardest-boiled doctor living couldn’t call it work for a girl to write a daily line to her one and only. (And while I’m on the subject, did I tell you that I conscientiously turned down fifty bucks for a series of five special articles from South America signed “Miss Rio de Janeiro”? Wasn’t I the obedient patient?)

There’ll be no nonsense on this trip, Davy. I can promise you that much. I’m going to be such a good girl you’ll be glad you’re not along with me. I shall keep my legs up and my hands down to recover from that ghastly “appendectomy” which almost made you a widower before you had tasted the doubtful sweets of married life, and which has left me so light and airy that I’m scared to go out on deck lest a puff of this riotous November wind should blow me overboard to the whales and sharks.

I promise to take my convalescence very seriously, doing only just enough writing to keep in practice. I shall bore you with my journalese descriptions of shuffle-board contests, deck sports, bridge battles at a twentieth of a cent and catty chit-chat about my fellow passengers. It won’t be a thrilling affair like the diary I kept for you when I was off on the Laubenthal case. Remember? It will be a modern imitation of your beloved Jane Austen, “in the inimitable style of Mary Llewellyn, whose daily paragraph in the Star has brought cheer and entertainment, etc., etc.” Perhaps we’ll read it over together when we play Darby and Joan in the twilight of our declining years.

Now, dearest, we are getting into deep water and I must catch the pilot before we drop him for good and all. The pilot —my last link with you and New York and civilization for a whole month. I don’t quite like it, Davy; my illness has left me a timid, stupid creature and I can almost find it in my heart to wish that I were safe back in my hospital bed with that lovely night nurse bending over me and handing me a soporific glass of hot milk. Or, better still, I wish that we were safely installed together in that brand new apartment of ours and that you could hold me in your arms and never let me go. But I suppose it’s all for the best that I should go off by myself and get well and strong again. It’s not for so very long—after all!

So good-bye, darling, and thank you once again for the flowers, the fruit, the books and the beautiful letter, and, above all, thank you for being just you and for wanting to marry a plain scarecrow who hasn’t even got a decent appendix to recommend her. I am wrapping Aunt Caroline’s fur coat around me and wishing it were you! I’ll post my first installment from Georgetown. God bless you, Davy; as I used to say when I was a baby—Mayangelskeepyou.

Your own,

P. S. I love you. MARY.

S. S. Moderna,

Friday, November 13th.

9:30 P. M.

Well, Davy darling, we’re really out to sea at last and rolling down to Rio in the approved style. It’s one terrible roll too, so you must excuse this wobbly writing. We’ve dropped the pilot, who brings a note from me to you with all my love; we’ve opened our letters, bon voyage telegrams and parcels; and we’ve all looked one another over with the usual first-day-out suspicion, hatred and distrust. And then, of course, some of us are very sick—oh, so green and gruesome! No, dear, not this one. I may be a poor weak woman, but seasick—never! Those trips up and down New York harbor to interview Peggy Hopkins Joyce have inoculated me against seasickness once and for all. But only thirty rather wilted looking individuals turned up for dinner and there are sixty-seven first class passengers on this tub.

And for all its modern name, it is a funny little tub, Davy. We knew when we picked it, of course, that it would be small and slow (as well as cheap), but there’s an atmosphere about it which reminds me irresistibly of a third rate summer resort on the Jersey coast. Four weeks of that, Davy. Just imagine! I can even smell the dried seaweed and antimacassars—not to mention more subtle dining room odors which are enough to cause even stouter hearts than mine to quail.

Of course, I could change my booking when I get to Rio, but the round trip rate is so good that I hate the idea of paying extra for my prescription. “Rest and sea air” is possible on any boat and I daresay I’ll feel better about this one tomorrow. You mustn’t blame me for being a bit blue just now, because it’s only natural I should feel that all the most attractive people (and one in particular) got off when the “All Ashore” sounded. However, I suppose I’ll soon settle down and reconcile myself to being without you, and life will be as simple as slipping on a negligée or a piece of orange peel.

What are you doing at this moment, I wonder? Writing to me, I hope, or playing bridge at the City Room with your “Front Page” cronies—anything but slaving away at that vile Brooklyn report which kept me so isolated, even in the hospital, that I almost began to believe it was not a report at all but a peroxide blonde with red polish on her finger nails. Your favorite combination before you met me, as you once admitted yourself!

But I must return to my muttons and tell you about my jolly little shipmates before they lose that first fine careless rapture of novelty. Most of the lady passengers look as though they were designed to fit the Writing Room in which this

journal is now being precariously penned. You know the idea, Davy; thin little tables with old, wobbly legs—a dove-grey carpet and pink plush curtains. Is there need for me to say that I shall not be lacking adequate chaperonage after that? The odd thing is that most of them are married too; the tired wives of tired husbands, either accompanying their better halves on rest cures or business trips. But they are not missing a trick, Davy, on a boat where everything is included, and while they are mostly too sick to eat or drink, they make up for it by staring disapprovingly at my open work stockings and the blue velvet tea-gown which was the outcome of my interview with Helen Mencken.

You see I’m beginning to be catty already!

So much for what you are pleased to call the “Women in Bulk.” Now for the men—and one in particular. (No, dear heart, there’s nothing to worry about; he’s over fifty and bald as a cantaloupe.)

Well, Davy, all my life to date, like that of the eminent Boston spinster, has been distressingly free from insult. But this afternoon I really thought that it had come at last. I was actually picked up by a man—and all without the slightest provocation. It did more to make me feel good than any of Dr. Klein’s tonics or Aunt Caroline’s pick-me-ups.

I had gone to the upper deck in order to find a nice quiet place for my sun cure, when he came up to me and said:

“I’ll arrange to have your chair put next to mine, if you don’t mind. I’m by way of being an invalid too and we really might have quite a lot of fun comparing symptoms. Mine was a gastric resection with adhesions—what was yours?”

In spite of the fact that I rather liked his voice, I flashed my eyes and my engagement ring at him in a manner which I’m sure you would have approved. Even on board ship a nice girl can’t be too careful.

“Oh, I saw the ring,” he said smiling. “In fact, I wouldn’t have spoken to you if I hadn’t. Unattached young ladies on board ship are a positive menace—especially to an old widower like me. Even the fact that I resemble nothing so much as an albino plum is no protection. I simply am not answerable for my actions at sea—the sunsets, moonrises, long halcyon days, foreign countries, all the glamour—”

“Glamour,” I snapped, misquoting from some trashy novel, “is a state of mind, not of geography.”

My retort seemed to please him mightily, for he immediately summoned the deck steward and said:

“Bring a chair over here, steward, and label it Miss—Miss—?”

“Llewellyn,” I replied grudgingly.

“Good; and my name is Burr.”

“Aaron?”

“No, but the next best, or rather the first best thing—Adam. A. B., Adam Burr, at your service—for just as long as you can keep me—from making a fool of myself, that is,” he added hurriedly and apologetically.

I found him very diverting and we chatted away until it was time to go and dress for dinner. I think I am going to like him. At least he’s nice and restful.

At dinner he turned up again at the captain’s table—where, thanks to the dear old Fox, I have one of the seats of honor. To my left is a safe old party named Lambert (of Lambertville, I expect), who sports a rather pretty wife, a flapper niece and a nice-looking young secretary who has dark hair, a black moustache like John Gilbert’s and who seems practically plastered to the flapper niece aforesaid. She is an uneventfully wholesome girl who answers to the name of Betty.

Then there is (or at least there was at lunch time) a widow, Mrs. Clapp, and her supposedly female companion who rejoices in the soft, clinging name of Miss Daphne. Demarest, but who looks like an Olympic discus hurler. Daphne is English and clips her g’s. Mrs. Clapp obviously adores her and is quite touchingly dependent on her Amazon. There’s also a Mr. Wolcott, white-haired, goateed and very much the courtly gentleman, and a Señor Silvera, so dark and Spanish and so sinister looking that you know he must be henpecked or kind to animals or that he practises the flute in his cabin. But whatever he does in private, he presumably does it in Spanish, for his English can only be described as splendidly null.

The twelfth chair is occupied by a funny little Cockney of about thirty-eight, who does nothing but blink his funny little eyes and attend to his food with a kind of fussy concentration which makes one wonder if he’s used to dealing with more than one fork.

Captain Fortescue is a peach. Nice, hearty, rather ponderously jovial, and always British—oh, so very British. He has a wife and five daughters in a place called Squaling or Ealing, or something like that, all of which rather dims the romance that might otherwise be inspired by his magnificent uniform and gold braid. Alas! his eyes are not for me. They are glued on the Lambert party, who are obviously the most consequential people on the boat and apparently our gallant skipper knows on which side his ship’s biscuit is buttered. And, incidentally, the Lamberts have invited the whole table to drinks in the smoking room tonight at ten. I know I shouldn’t—but! Well, it’s the first night out and a girl’s only young once, you know, and not so very young at that!

In the meantime, you ought to feel perfectly comfortable, my pet. Your Mary is safely launched on the deep blue sea with not a playmate under forty in sight, unless one happens to show himself when the sea gives up its sick; not a familiar name on the passenger list and the one eligible male obviously hanging on the smiles of a rich young flapper.

And so, as I said before—and as Kipling said several times before me—we go rolling down to Rio!

Here comes my Adam to fetch his Eve—or, as he calls me, not very flatteringly, his safety valve! Would you believe it, the sun on the upper deck must have caught his bald pate because it has actually turned a delicate pink? In November too! What fun I am going to have watching the “plum” ripen into gloryous crimson maturity. And keeping the flies off it according to our contract! That’s a new rôle for a promising young girl reporter.

And so to the bar, but not, I hope, to cross it.

No more now.

Stateroom,

Saturday, November 14th.

2:10 A. M.

Did I say “no more,” Davy? Did I say that? Did I also say—oh, my God, what didn’t I say? And what haven’t I to tell you now?

I tried to send off a radio to the paper, but it was promptly suppressed. If only you and I had arranged a private code, Davy, we’d have the greatest scoop in our careers tonight.

You’ll certainly have had the news long before this frantic scrawl reaches you, but I’m going to try and collect my scattered wits sufficiently to keep as full a record as I did for the Laubenthal case. You remember what a help that turned out to be in solving the mystery—and here on board this very ship, Davy, is a mystery that makes the “L” case look as simple as a jigsaw puzzle of only three pieces!

And won’t Aunt Caroline crow! She’ll say it all came from taking a boat that sailed on Friday the thirteenth. And she won’t be so far wrong either. Since sleep is now impossible, I’ll begin at the beginning, or rather where I left off earlier this evening. (Was it really this evening—just about four hours ago? Seems like a million aeons since I had a moment of peace or tranquillity!)

Probably the first half of my story, at least, is irrelevant and immaterial, if not incompetent, but it just might supply a clue, so here goes.

You remember how I said that the Lamberts had invited our whole table to the smoking room for drinks at ten? Well, I drifted in with Adam Burr a few minutes after I’d finished writing to you and found Mrs. Lambert sitting in state with old Wolcott. Mr. Lambert was playing bridge with the funny little man I described earlier whose name turned out to be Daniels,—Mr. Burr (who had gone out to fetch me while he was dummy), and another man whom I hadn’t seen before. In addition there was a steward behind the bar, but I am quite positive that there was no one else in the room.

Mrs. Lambert greeted me as I came in, so I sat down with her and the courtly Wolcott and our positions were like this:

My hostess was most affable and we became quite girl-to-girl on the subject of my special arti

cles, which she always reads over her Sunday breakfast. She is one of those women who are actually about thirty-eight, don’t look a day over twenty-eight, and act all of eighteen. Still, she was pleasant enough and old Wolcott took his cue from her and together they flattered me so that I really began to believe that there is something in the power of the press—after all.

Mrs. Lambert asked me if I’d like to order a drink now or wait until the bridge players joined us. They looked as if they were just about to finish a rubber so I naturally said I’d just as soon wait a while. From time to time I managed to escape from her dithyrambs and strolled over towards the bridge table in order to watch the play. Although the stakes were not high, everyone seemed to be very intent on the game. So much so that I was introduced only in the most casual manner to the member of the party whom I hadn’t met before, a Mr. Robinson, I believe his name was. As I remember him, he was an uneventful person, of any age between thirty and fifty; cleanshaven; wore glasses, and had thick sort of brownish hair and a wonderful coat of tan. This, he explained in rather a squeaky, high pitched voice by saying it was the result of a prolonged vacation in Florida. I can’t for the life of me remember his saying anything else.

It was not long before I realized that something was rotten in the game of contract—or at least, that Mr. Daniels was not very well satisfied with his partner’s play. They had, apparently, won two rubbers more by good luck than good judgment, but now things were beginning to go against them.

“Well,” snapped Daniels in pure Londonese which I will not attempt to reproduce, “since I’m incapable of getting my partner to give me the correct lead, I propose a drink, if you’ve no objection, sir,”—this to Mr. Lambert. “Now, I have the recipe for a gin rickey—may I order one all around?”

“No, no,” cried Mr. Lambert hospitably. “The party is on me, but I’ll buy anything an Englishman suggests in the shape of a new concoction.”

Death Goes to School

Death Goes to School Hunt in the Dark

Hunt in the Dark The Cases of Lieutenant Timothy Trant (Lost Classics)

The Cases of Lieutenant Timothy Trant (Lost Classics) Death for Dear Clara

Death for Dear Clara S.S. Murder

S.S. Murder Death and the Maiden

Death and the Maiden The Grindle Nightmare

The Grindle Nightmare Cottage Sinister

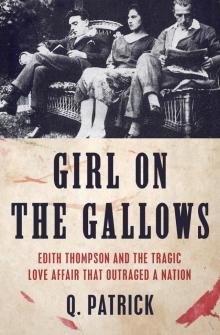

Cottage Sinister The Girl on the Gallows

The Girl on the Gallows